The fact that many founders and leaders in the software industry did not major in computer science is a subtle theme. They were music students. Not in a passive manner, either. Before they ever touched a company pitch deck, they spent years writing, performing, and practicing.

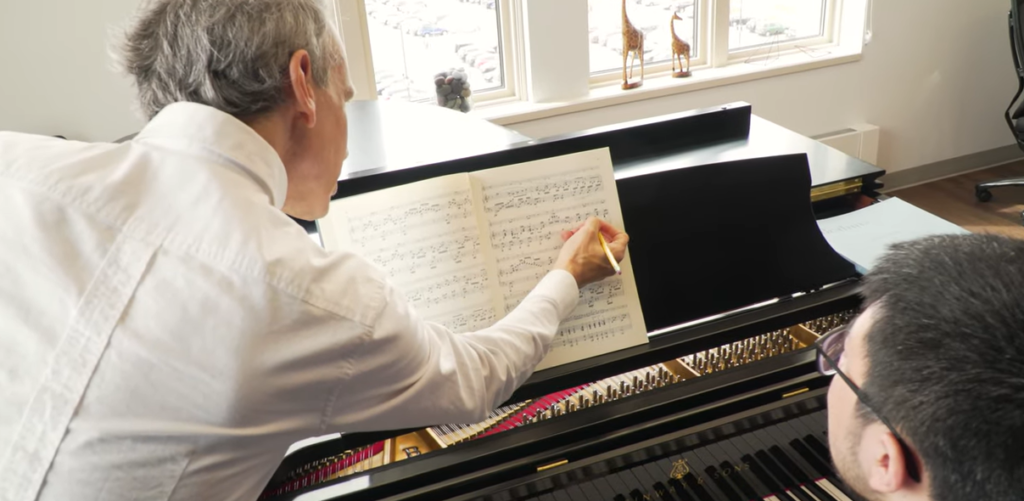

The transition from orchestra pit to open office plan may seem abrupt to an outsider. However, the dynamics within a product sprint frequently resemble those in a quartet rehearsal. Both need active listening, real-time adjustment, and the layering of concepts without overpowering the signal.

Students who major in music acquire a mental agility that is surprisingly useful in high-stakes tech settings. They are taught to decipher complexity while maintaining a sense of order. Ravel requires deep thinking, emotional navigation, and timing in addition to performance. Their later leadership style is shaped by these practices.

| Topic Element | Description |

|---|---|

| Central Idea | Music majors are emerging as influential tech leaders due to their unique cognitive, emotional, and collaborative skills |

| Skills Overlap | Creativity, problem-solving, resilience, and communication — traits cultivated in music — align with tech leadership needs |

| Industry Interest | Tech firms increasingly value “nontraditional” hires, including musicians, for their adaptive thinking |

| Notable Figures | Google co-founder Larry Page studied music and attributes part of his innovation mindset to it |

| Cultural Insight | MIT and Berklee collaborations show growing institutional belief in blending music and tech for innovation |

One startup founder told me that he learned how to bounce back from setbacks—on stage, mid-piece, with a spotlight—thanks to his degree in music. He claimed that his resilience had better prepared him than any management course. It was also observed by his team. When launch plans changed at the last minute, he just modified the tempo instead of freaking out.

Such serene agility is uncommon. And incredibly efficient.

Learning music fosters endurance in addition to skill. To become proficient at phrasing, a violinist must practice for years. This type of mental and emotional fortitude later manifests in leaders who persevere when financing falters or code malfunctions. They adjust themselves and continue.

The thought processes of musicians are especially inventive. Although they are dedicated to structure, they are at ease with uncertainty. Any excellent technical solution or user experience design is based on this duality—improvisation within form. You don’t just use formulas to solve problems; you also use your intuition.

There is also empathy.

For thousands of hours, musicians wait to see what the other members of the ensemble will do. They pay attention, react, and modify. This develops a social intelligence that is very adaptable to different teams. Even when there are differences in technical understanding, this type of intuition leads to extremely effective teamwork.

Leading tech businesses are taking notice. Employers are no longer using standard resumes. They are focusing on how people lead, think, and adjust. It’s possible that a developer who is also a symphony conductor will do better than a peer who is more skilled technically but has never mastered deep listening.

I’ve encountered CTOs who attribute their ability to manage engineers to their training in music. According to one, conducting helped him learn how to lead without commanding, which is very useful in decentralized product teams.

Indeed, there are anomalies, such as Larry Page, a music scholar who went on to co-found Google. However, the larger change is cultural. Because musical thinking improves technological results, organizations like MIT are incorporating music into innovation pipelines—not for amusement.

In those courses, students collaborate to construct wearable audio feedback or AI interfaces that use rhythm recognition. However, the product isn’t what sticks. It’s the fluency in multiple disciplines. the capacity to communicate design, code, and emotion simultaneously.

Collaborations between tech and music developed during the pandemic. Teachers were compelled to reconsider performance due to remote learning. Something enduring emerged from such disruption: musicians were remarkably flexible. They adopted new technologies, such as digital composition and video instruction. Fast-growing tech teams specifically want the same flexibility.

Emotional intelligence may emerge as the hallmark of successful leadership in the years to come. Tech has been effective. It must now be human.

Leaders who are able to include empathy into their approach will succeed better than those who can merely maximize output. Planning sessions, team input, and product decisions all benefit from the emotional nuance that musicians, who are trained to create mood and narrative through sound, contribute.

It’s not about substituting artists for engineers. It’s about recognizing that they could be the same individual.

Having a founder who truly understands harmony may improve meetings, make pitch decks feel more cohesive, and foster a more natural culture, especially for early-stage firms. It’s not fluff. Infrastructure is that.

One of the most powerful pitches I ever heard at a demo day came from a founder who had majored in classical piano. Her language was straightforward and her slides were straightforward. However, her speech pattern and the way she created tension and used data to relieve it felt like a perfectly timed sonata. Investors reacted right away.

Companies are not only gaining diversity by incorporating music-driven thinking into the IT industry, but they are also gaining a distinct advantage during unpredictable times. These leaders are aware of when to slow down, pick up speed, and pay attention.