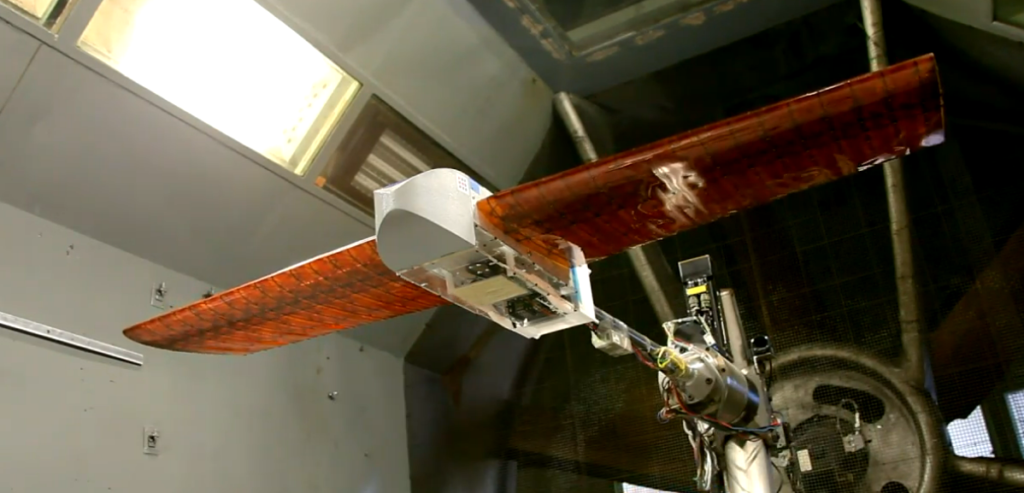

The prototype doesn’t appear to be a device ready to permanently alter flight at first inspection. Then, however, something subtle occurs. Its wings flex without any motors or hinges, causing the edges to ripple very little. It adapts, reacting with grace rather than mass or loudness. It’s the kind of change that sticks with you after you’ve seen it.

Researchers are discreetly developing aircraft that can change their shape in midair in engineering labs, a development that previously believed limited to science fiction. Sleek planes with retractable flaps are not all that these are. These are memory-equipped aircraft with structures that can bend, adapt, and self-correct while in flight.

These designs seek to emulate the best fliers found in nature by substituting flexible materials and intelligent composites for traditional flaps and hinges. Imagine a butterfly making a mid-glide adjustment or a falcon tucking its wings in for a dive. Instead of just copying, these new planes enhance the concept by fusing mechanical accuracy with biological grace.

Recent years have seen the introduction of morphing-wing prototypes that move with silent intelligence by organizations such as MIT and NASA. Aerodynamic pressure and internal programming determine their shapes rather than hydraulic force. Particularly with UAVs where stealth and weight are crucial, it works incredibly well. For surveillance operations, these designs are especially advantageous because they do not require noisy actuators.

Table: Key Context on Shape-Shifting Aircraft

| Feature | Description |

|---|---|

| Technology Name | Morphing Wings / Adaptive Compliant Wing |

| Core Innovation | Aircraft structures that change shape mid-flight for efficiency and control |

| Key Institutions Involved | NASA, MIT, DRDO, U.S. Air Force, Boeing, DARPA |

| Materials Used | Shape memory alloys, elastomers, smart composites, lattice structures |

| Applications | UAVs, fighter jets, future commercial aircraft, space systems |

| Current Status | Flight-tested in drones; under development for military & aerospace use |

| Reference | https://news.mit.edu/2019/engineers-demonstrate-lighter-flexible-airplane-wing-0331 |

A test film of one such prototype caught my attention; under a thin layer of polymer, its skin flexed like muscle, moving smoothly in response to changes in air pressure. It resembled something living rather than a computer. What’s at risk was highlighted by that moment, which was unexpectedly emotional for something so technical. These devices adapt, not just fly.

Through the integration of lattice-based substructures, engineers have produced components that are extraordinarily robust and adaptable. Because each tiny module functions similarly to a cell in a live organism, planes can twist, extend, or narrow to suit the necessities of flight. Among the results is a noticeable increase in fuel efficiency. They also have a longer range and much less turbulence.

In recent experiments, drones with wings that change shape were able to fly steadily in windy conditions where conventional designs would have had trouble. This provides a strategic edge for military applications. However, it promises quieter engines, smoother landings, and aircraft that can change shape during takeoff or cruise, eliminating the need for a fixed speed-safety trade-off in commercial aviation.

Teams like those at DARPA and Boeing have investigated even more ambitious ideas through strategic alliances. One has rotor blades that stretch for more lift in midair and retract for cruising at high speeds. Another, which is currently in the early stages of development, envisions a spacecraft that can change shape as it travels through various planetary atmospheric densities.

Engineers are now creating responsive systems instead of static machinery by utilizing shape memory alloys and sophisticated elastomers. Robots in the conventional sense are not what these are. These are buildings that “know” what they’re doing, responding to airflow or load stress passively and occasionally instinctively. It’s similar to how a tree limb bends in the wind without breaking.

These developments are more important than ever in the context of climate-conscious design. Lighter aircraft consume less fuel. Adaptive designs are very efficient to maintain since they require fewer moving parts. Also, the entire process of creating an airplane becomes unexpectedly economical and scalable because the skins and cores of these wings can be 3D printed.

In real-time military exercises, India’s DRDO has already launched a drone with morphing wings. Adaptive camouflage and flying patterns are two areas in which the U.S. Air Force has made significant investments. NASA is now working on improving prototypes that react to variations in lift, drag, and vibration on their own without the need for pilot input.

The advantages are very evident for early-stage aircraft designs. Faster prototyping cycles, fewer mechanical failures, and more agile designs are the results of reducing weight while increasing performance capabilities. The design concepts are permeating every facet of aerospace innovation, even though commercial passenger planes may not yet resemble their shape-shifting siblings.

Standing next to one of the experimental wing segments—polymer skin stretched taut over a flexible, fractal-like framework—during a recent visit to an aerospace exhibition. With one hand, the engineer next to me twisted the panel while grinning. It was like memory foam, flexing and returning. She stated, “It doesn’t break.” “It picks things up.”

The future of aviation may be shaped by this kind of learning, which is integrated into structures rather than software, in the years to come. The possibilities extend well beyond Earth’s skies, from solar drones that can reorient their wings to more effectively seek energy to Mars rovers with bodies that can change to overcome tough terrain.

It is this shift’s sensibility as much as its science that makes it so fascinating. This method of flying is modeled after the adaptability of nature—machines that react to their surroundings in a clever and natural way rather than fighting against them. For the first time in the lengthy history of flying, shape might be just as important as speed.

It turns out that the future of flying may not soar past us at supersonic speed, but rather glide, twist, and adapt while humming intelligently in the background. It won’t be decades from now. Piece by responsive piece, it is gradually coming together on its own.