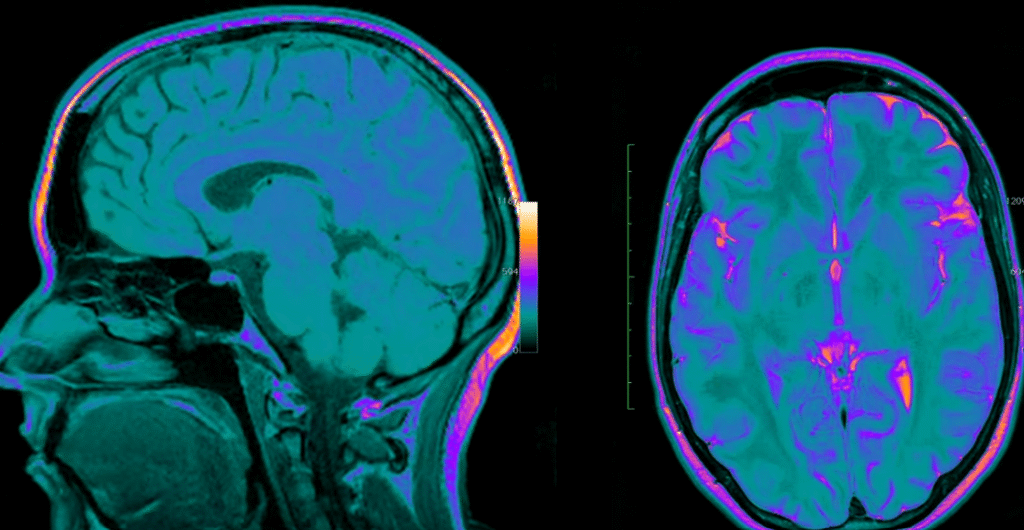

The brain is a live network that constantly reshapes, prunes, and strengthens connections every time we learn a new ability or remember a concept. It is not a static collection of memories. Neuroscience has demonstrated that all information is constructed by biological rewiring, which is quite similar to how a sculptor forms clay—purposeful, patient, and teeming with possibility.

This concept has become remarkably clear because to studies conducted by Professor Takaki Komiyama at the University of California, San Diego. His team’s research, which was published in Nature, charted the physical changes that learning brings about in the brain’s circuits. They found that during learning, two important areas—the thalamus and motor cortex—improve their communication by amplifying pertinent messages and blocking out irrelevant ones. This method provides insight into how the brain gets extremely efficient with repetition and is remarkably successful in increasing speed and precision.

Therefore, learning is the active building of understanding rather than the passive absorption of knowledge. The brain’s capacity to reorganize itself over the course of a lifetime is known as neuroplasticity, according to neuroscientists. It implies that development is not limited to childhood. Adults are also capable of learning new languages, changing their mental landscapes, and regaining cognitive function following an injury. This realization has had a significant impact on personal growth, treatment, and education by serving as a constant reminder that possibility is limitless.

| Name | Professor Takaki Komiyama |

|---|---|

| Profession | Neuroscientist, Researcher, Professor |

| Nationality | Japanese-American |

| Known For | Groundbreaking research on neuroplasticity and motor learning |

| Institution | University of California, San Diego |

| Education | Ph.D. in Neuroscience, University of Tokyo |

| Notable Work | Study on thalamocortical pathway rewiring during learning |

| Recognition | Published in Nature and Science, supported by NIH and NSF |

| Reference | https://neurosciencenews.com |

This is brilliantly explained by Dr. Hila Goldberg of the National Institutes of Health: “Every time you think differently, you change your brain.” According to her research, having a positive outlook can significantly enhance brain adaptability. This scientific foundation for optimism lends credence to what educators today refer to as the growth mindset, which holds that intelligence can increase with hard work, curiosity, and persistence. It is a biological fact rather than merely a catchphrase.

These discoveries are changing the way that lessons are taught in classrooms. Because they activate several brain regions at once, neuroscience supports active learning techniques like problem-solving, discussion, and application. Understanding is improved by the process, which builds a dense network of brain connections. Because it promotes deeper engagement—the brain learns best when it works, not when it watches—it is very novel.

For example, retrieval practice requires pupils to remember material instead of rereading it. This battle is a desirable challenge that improves memory, even if it may seem uncomfortable. Recalling strengthens brain connections, increasing the information’s durability. According to neuroscientists, it’s similar to working out a muscle: the harder the exercise, the stronger the growth.

The complex interplay between emotion and learning is further highlighted by Komiyama’s findings. The amygdala tells the hippocampus to further encode memories when people are curious, excited, or even under mild stress. Emotion helps events stay together like glue. Teachers that incorporate humor, empathy, and storytelling into their courses take advantage of this biological function, which makes learning both highly effective and pleasurable.

Leading the charge to apply these findings to teaching is Paul Main, the creator of Structural Learning in the UK. His method is centered on matching instructional techniques to the way the brain stores, processes, and recalls information. He claims that instead of teaching a subject, you are creating a brain that comprehends it. His comparison of the brain to a garden and learning to its cultivation is especially illuminating. When given consistent attention, it thrives, but when neglected, it overgrows with distractions.

The ramifications go well beyond the classroom. Neuroscience shows how professional athletes hone their motor skills via practice. The brain’s motor pathways grow much quicker and more efficient as Lionel Messi or Serena Williams train. Only the most effective connections remain when redundant brain pathways are eliminated. It appears that excellence is a combination of neurological precision developed over time as well as discipline.

Neuroplasticity is also used by musicians and artists to create in the creative professions. While visual artists use the prefrontal cortex to transform their imagination into form, composers use both hemispheres of the brain to create tunes. Because of the cooperation between biology and intuition, creativity is quantifiable while being incredibly human. Without lessening its awe, neuroscience has provided a language for the enigma of inspiration.

But the field also cautions against oversimplifying. Reality is distorted by persistent neuromyths, such as the notion that people only employ 10% of their brains or that people are exclusively “left-” or “right-brained.” Neuroscientists stress that learning requires cross-regional collaboration. The brain functions not as a solitary instrument but as a symphony. Understanding is the result of the distinct contributions made by each component to memory, emotion, and reasoning.

The uses of neuroscience in society are becoming more apparent. Academic results in schools that incorporate brain-based practices—such as physical exercise, mindfulness, and spaced learning—are noticeably better. Nutrition and sleep are also acknowledged as critical elements of brain health. The brain replays and integrates everyday memories into long-term memory during deep sleep. Learning continues to be a lifelong process because nutrient-rich diets promote neurogenesis, or the creation of new brain cells, and synaptic strength.

Similar ideas have started to be incorporated into corporate training programs. Organizations such as Google and Deloitte utilize neuroscience-based learning frameworks that reinforce employee knowledge through emotional involvement, reflection exercises, and repetition intervals. The method acknowledges the biology of attention and the brittleness of memory, making it both practical and humanizing.

Beyond scholarly theory, Komiyama’s research gives optimism. Patients recuperating from stroke or neurological illnesses may benefit from his mapping of how brain circuits remodel during learning. One day, medical professionals may be able to assist the brain regain previously thought-lost abilities like voice, mobility, or memory by focusing on the same pathways that facilitate learning. This potential transforms scientific research into real healing, which is very advantageous for rehabilitation.