Michael Ryan discusses AI and humor in a way that is both fascinating and cautious, like to someone elucidating a cosmic conundrum. As a researcher implanted at Stanford, Ryan is looking at whether machines can understand the inner architecture of comedy rather than just testing whether they can copy jokes. After all, it’s the rhythm, the context, and the absurdity woven within the truth that make us laugh, not simply the words.

His initial investigations demonstrated the true complexity of this problem. When asked to compose a joke, ChatGPT and other AI models often fall back on cliched internet humor, inappropriate gender stereotypes, or outdated one-liners. They do, however, occasionally hit something strangely amazing. Ryan and his crew have been especially interested in that uncertainty.

Ryan has developed a framework for AI-generated humor by working with other researchers and stand-up performers. Giving the model structure, direction, and an audience-aware sense of timing is equally as important as training it on billions of punchlines. Ryan has stated, “It’s not about coding laughs.” “It’s about teaching a machine to walk a room—digitally.”

But it’s a steep challenge. Comedy requires timing that can be incredibly accurate, influenced by room tone and millisecond beats. Even though they are extremely effective with data, machines still have trouble with subtleties. The chuckle that springs from a sudden silence or a judicious look? Syntax by itself cannot reverse-engineer it.

However, some experiments are causing many to reconsider. Ryan’s AI-generated punchlines placed in the top 87th percentile when compared to human-written responses in a test that was designed to resemble the Quiplash game. That outcome was especially unexpected—not because AI outwitted professional comedians, but rather because it outperformed the majority of non-comedians. AI comedy didn’t only fit in with the abundance of rehashed content on the internet; on occasion, it stood out.

| Bio Detail | Information |

|---|---|

| Name | Dr. Robert Walton |

| Profession | Researcher, Performance and AI |

| Current Role | Dean’s Research Fellow, Faculty of Fine Arts and Music |

| Affiliation | University of Melbourne |

| Field of Expertise | Human–Robot Interaction, Performance, Comedy, AI |

| Known For | Research on teaching robots non-verbal humor and comedic timing |

| Education | PhD in Performance Studies (related disciplines) |

| Research Focus | Comedy, audience feedback, embodied AI |

| Location | Melbourne, Australia |

| Reference Website | https://finearts-music.unimelb.edu.au |

In the meantime, comedian Karen Hobbs consented to participate in this sociological experiment as a test subject. With only a screenplay created by ChatGPT, she took the stage in London. There were giggles, eye-rolls, and a tense stillness during her presentation, which was a mix of satire and science. Hobbs’ quip about the glue stick acting like lipstick hit with a bewildered thud. “I’ve literally never felt more stupid in my life,” she continued, half-smiling. It was the honesty of the line, not the joke, that made people chuckle. Unscripted and vulnerable, that moment brought to light something that no computer can replicate.

Former New Yorker cartoon editor Bob Mankoff contends that humor and human frailty are closely related. Good jokes frequently convey social tension, unease, or nervousness. AI is immortal; it is not concerned about rejection or humiliation. However clever the programming, that lack of risk dilutes its humorous realism.

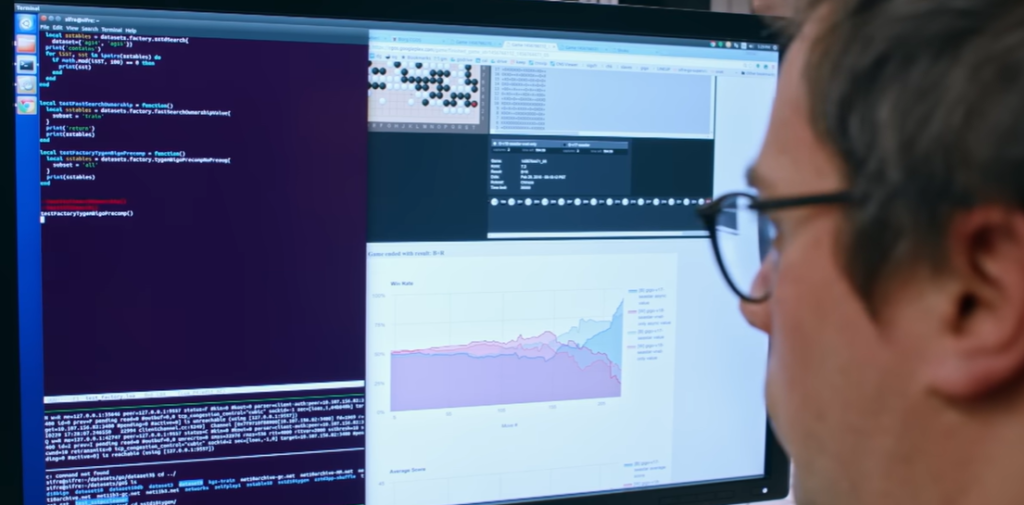

However, scientists like Dr. Robert Walton are looking beyond humor. Walton is training a group of robots in physical comedy at the University of Melbourne with a grant. These bots are not humanoid, and instead of telling jokes, they execute them, frequently without using words. Movement, stumbles, and exaggerated emotions are all part of their acts. According to Walton, a pratfall or a well-timed misstep might spark laughs instead of a punchline.

These robots, he says, are like “babies learning to read the room.” They have been designed to recognize changes in posture, track head tilts, and identify laughter. Their responsiveness significantly improves with time, resulting in more involved performances. Walton wants to learn more about how humor works through action and intention, not to take the place of comedians.

A more doubtful perspective is provided by Alison Powell of the London School of Economics. Powell, a veteran improv performer, highlights that a large portion of AI’s current humor is taught using stolen creativity. She cautions, “Comedians should be concerned.” “A significant portion of this training data is unapprovedly scraped from YouTube, Reddit, or TikTok.” For platforms such as OpenAI, it is a battlefield of ethics and law.

The worry is only heightened by the lawsuit brought by The New York Times, which claims that OpenAI has “purloined millions” of dollars’ worth of intellectual property. Powell contends that AI’s contribution to comedy might be more about combining pre-existing talent than it is about producing original content. This tendency runs the risk of reducing creative expression to formulas.

There is yet hope, though. According to USC cognitive researcher Drew Gorenz, AI can be useful even if it doesn’t take the position of performers. Its humorous output can be surprisingly effective in unexpected places, such as AI customer support systems taught with mild wit to reduce tension or caring robots using light humor to improve patient spirits. He clarifies that the goal is to comprehend the value of humor rather than have robots perform at comedy clubs.

Even seeing AI fail has a certain charm to it. We laugh at a robot’s awkward jokes because it’s trying, not because it’s witty. And that effort connects with something genuine, regardless of how artificial it may be. Audiences can be understanding, as Ryan’s research demonstrates. As long as the machine continues to learn, they are prepared to meet it halfway.

Celebrated comedian Simon Rich once co-wrote ridiculous poems and headlines using an unreleased OpenAI model. The outcomes? Terribly excellent. “Director insists on using real Batman for $200M production,” was one AI-generated Onion-style headline. It was organized like a real joke and extremely satirical. Rich said, “It gave me nightmares.”

AI is quickly learning to emulate the form of humor, even though it still can’t provide a really human performance—one that is based on years of failure, ego wounds, and funny instinct. In an effort to match speech rhythm and tone with humorous timing, researchers are already investigating models with audio capabilities. If they are successful, AI might start taking part in real, humorous conversations in addition to creating material.