Years ago, I witnessed a test flight in which only one engine was powered by fuel derived from algae. The half-old, half-new symbolism was subtle but powerful. A glimpse of our current location and future prospects. Although that flight didn’t garner much attention, it was a turning point that seems particularly important now.

In 2021, All Nippon Airways quietly ran a domestic flight using only certified sustainable aviation fuel derived from algae. For those who followed energy innovation, it felt like a milestone that had finally arrived—one shaped by decades of scientific groundwork and strategic coordination—even though it didn’t come with big banners or striking visuals. The essential component? tiny algae. These microscopic organisms, which are cultivated in either closed bioreactors or open ponds, store lipids that can be transformed into high-density bio-jet fuel that is strikingly similar to conventional kerosene.

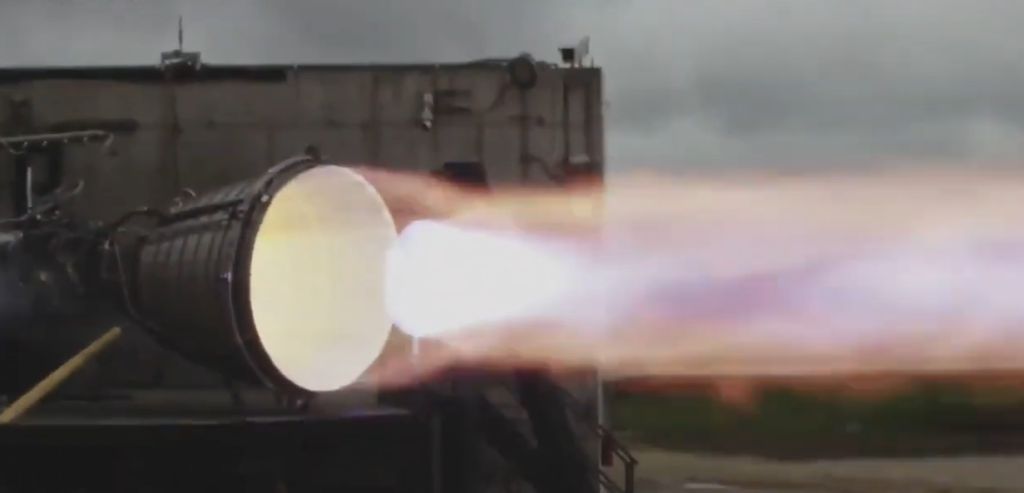

The appeal is clear. Algae consume carbon dioxide throughout their life cycle, grow swiftly, and do not compete with food crops. As a result, it is not a carbon-spewing resource but a carbon-capturing one. This biofuel is a drop-in substitute, which means it can run through current fuel lines and power engines without any changes, unlike hydrogen or electric propulsion, which call for infrastructure overhauls.

Key Facts: New Rocket Fuel Made from Algae

| Detail | Information |

|---|---|

| Fuel Source | Microalgae (e.g., Botryococcus braunii) |

| Technology Developer | IHI Corporation (Japan) |

| First Commercial Flight | ANA (All Nippon Airways), June 2021 |

| Certification Achieved | ASTM D7566 Annex 7 (May 2020) |

| Fuel Type | Sustainable Aviation Fuel (SAF); drop-in replacement |

| Advantages | Non-food crop, high energy yield, fast growth, no engine modification |

| Industry Partners | ANA, NEDO, Honeywell UOP, Solazyme, United Airlines, Airbus |

| Remaining Challenges | Scaling production, cost parity with fossil fuels |

| External Reference | ANA Group Press Release |

The fuel passed the most significant regulatory requirement by obtaining ASTM D7566 Annex 7 certification. Although it may sound dry, that approval is crucial. Commercial airlines wouldn’t even think about implementing it without it. It made the fuel not only feasible, but also feasible to fly. With significant support from NEDO, a government-backed innovation agency that has covertly funded many of Japan’s sustainability pivots, IHI Corporation of Japan created the first certified batch.

ANA made the audacious but well-considered decision to incorporate algae fuel into a legitimate commercial route through strategic alliances and meticulous research and development. That choice struck me as especially brave, not because it was dangerous from a flight-safety standpoint, but rather because it represented a conscious break from PR jargon and a move toward long-haul thinking. This was a test of consistency rather than a one-time press event.

Similar technologies have also been invested in by United Airlines and Airbus, frequently through partnerships with Honeywell UOP and businesses like Viridos. Despite their commercial motivations, these endeavors are governed by explicit sustainability regulations. The trajectory is on the right track, despite the fact that algae fuel is still more costly than conventional jet fuel. Prices are gradually declining. Processes for cultivation and refinement are being optimized. Additionally, consumer awareness of the climate cost of aviation is rapidly increasing.

Aerospace manufacturers are not merely experimenting when they work with academic institutions; rather, they are validating a decarbonization path that fits their operational realities. Algae-based fuel, in contrast to other futuristic fuel types, is already available and operating covertly. And that’s its greatest strength, in a way.

The readiness of this solution is what makes it so inventive. It doesn’t require airlines to re-engineer or airports to rebuild. It just plugs in. In an industry with tight safety margins and highly interdependent systems, that kind of smooth integration is extremely valuable.

Sustainable aviation fuel has progressed from concept to contract during the last ten years. Airlines are now securing multi-year agreements for blends based on algae. Incentives are being developed by governments. In order to handle and store these fuels, some airports are even building specialized infrastructure. Scalability in this setting becomes a matter of investment rather than creativity.

There are still challenges. At this time, algae fuel is not sufficiently affordable to rival traditional kerosene on a large scale. Furthermore, there are still environmental restrictions on its cultivation; it still requires a lot of energy, water, and processing facilities. However, those limitations are being overcome by more intelligent engineering and decentralized production techniques as demand increases and pilot projects demonstrate the technology’s dependability.

The way that algae fuel subverts popular notions of clean energy is especially intriguing. It’s not as flamboyant as electric jets or as avant-garde as turbines that run on hydrogen. But it’s reliable, strong, and incredibly efficient. It illuminates the way for the future while fitting into the infrastructure of today. And that’s a breakthrough for a sector that is infamously resistant to change.

The more I study the potential of algae, the more I see that some of the most revolutionary breakthroughs happen in the background. At first glance, they don’t always appear revolutionary. They just work—and continue to work. Furthermore, it’s too late to label them experimental by the time you realize they’ve completely changed an industry.

These days, algae is more than just a favorite in research labs. Passengers are in the air. It’s gaining favor with airlines. Obtaining certifications is the goal. Additionally, it might eventually aid in lowering emissions from a sector that is frequently charged with delaying climate action.