It has always been a fight of intelligence, perseverance, and good fortune to cure cancer. Something quite unusual is now joining it: algorithms that are able to learn, adapt, and find patterns that even the most seasoned scientists are unable to see. An ambitious group of scientists and entrepreneurs is rethinking the battle against cancer through the use of artificial intelligence in data centers and biotech labs. They are not mistaken in their optimism. AI is reprogramming the concept of discovery in addition to speeding up research.

This new generation of medical pioneers is exemplified by Chris Gibson, the dynamic co-founder of Recursion Pharmaceuticals. With millions of cellular tests conducted every week and the data fed into machine learning models that uncover hidden connections between genes, chemicals, and illnesses, his company sits at the intersection of biology and computing. Gibson’s method is incredibly successful; it replaces years of trial-and-error testing with simulations that can surprisingly accurately anticipate which drugs can halt the spread of cancer.

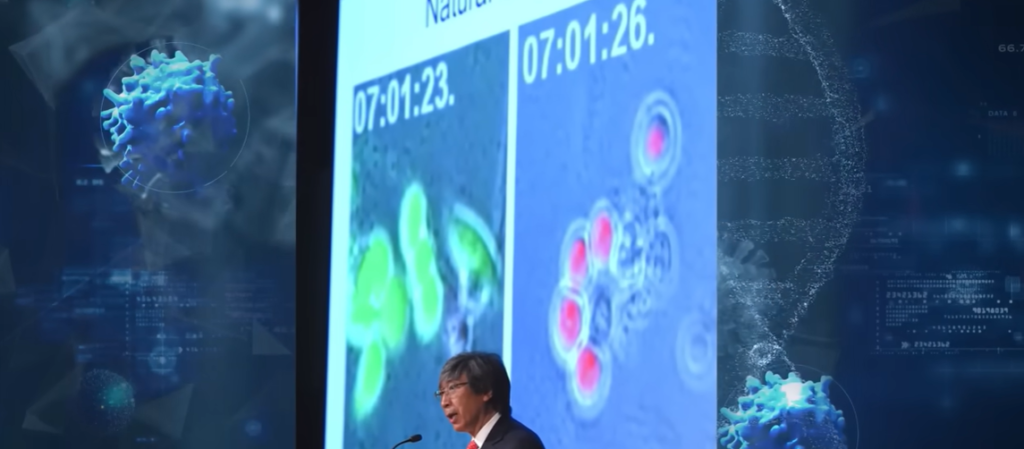

Recursion’s infrastructure is what sets it apart from the competition. More than 65 petabytes of data from experiments carried out in automated labs are processed by the company’s BioHive-2 supercomputer, which was constructed in partnership with Nvidia. Imagine a hive of robotic arms, each one pouring microscopic data into constantly-active neural networks, photographing cell responses, and transferring substances. Recursion aims to find medication candidates that might otherwise go undetected with this symphony of automation.

Gibson’s team hopes to greatly accelerate and reduce the cost of cancer medication research by utilizing advanced analytics. Before a single medicine is authorized, traditional pharmaceutical research might cost billions of dollars and take more than ten years. By enabling high-speed pattern identification across genetic and chemical data, artificial intelligence (AI) alters that equation and finds the most promising leads in days as opposed to years.

Profile Overview: Dr. Chris Gibson

| Category | Detail |

|---|---|

| Full Name | Chris Gibson |

| Profession | Co-founder and former CEO of Recursion Pharmaceuticals (Tech-Bio Company) |

| Nationality | American |

| Known For | Leading one of the most ambitious efforts to deploy AI and automation in drug discovery, especially targeting complex diseases like cancer |

| Organization | Recursion Pharmaceuticals (Salt Lake City, USA) |

| Achievement | Spearheaded development of Recursion OS platform and BioHive-2 supercomputer to process massive biological data for drug discovery Fortune+2recursion.com+2 |

| Focus Areas | AI-driven target identification, phenomics, high-throughput wet labs, oncology and rare disease drug pipelines Genetic Engineering & Biotechnology News+1 |

| Reference | https://www.recursion.com |

This strategy has sparked a fresh round of rivals. The same goal—algorithmic discovery at previously unheard-of speed—is being pursued by businesses like Insilico Medicine, managed by Alex Zhavoronkov, and Insitro, created by AI pioneer Daphne Koller. They have made quite great development. It was previously unimaginable that Insilico’s AI-designed medication for lung fibrosis went from computer model to human trials in under 18 months. Each of these innovations demonstrates how data-driven approaches have the potential to transform the way diseases are treated.

The enthusiasm is not limited to startups. With incredible resources, tech giants are joining the race. Google’s DeepMind is using its AlphaFold algorithm, which makes remarkably accurate protein structure predictions, in oncology research. To speed up clinical data processing, Microsoft’s AI health group is working with large hospitals. GPUs are now the engines of medical research thanks to Nvidia, which formerly powered video games and now powers biological computing for companies like Recursion. This collaboration between technology and medicine is especially advantageous since it enables fields that previously appeared to be completely unrelated to work together.

There are significant ramifications. Consider an artificial intelligence platform that can forecast a tumor’s next mutation, model its evolution, and recommend the best course of treatment before the cancer adapts. Oncology might become a proactive science instead of a reactive one with such methods. In order to ensure that medicines are focused, effective, and noticeably less harmful, doctors could customize treatments based on each patient’s molecular profile as well as the type of cancer.

This industry offers investors a wealth of opportunities, both monetary and humanitarian. Venture finance is flooding the worldwide AI-oncology sector, which is predicted to grow dramatically and be valued at close to $2 billion in 2023. Visionaries like Reid Hoffman of LinkedIn and Jensen Huang of Nvidia are placing significant bets on these developments. Their support demonstrates faith that the combination of biology and data can produce discoveries where conventional research has failed.

However, there is realism mixed in with the hope. Like conventional chemicals, many AI-discovered medications nevertheless fail clinical trials. Success in the human body is not always correlated with success in silico. Cancer is still incredibly complicated and has the potential to change more quickly than our existing models can account for. However, because AI is constantly learning, every setback contributes to future advancements. Predictive power and reliability are progressively increased when each dataset and error is converted into a lesson that is incorporated into the upcoming model generation.

The “lab-in-the-loop” strategy employed by businesses such as Genentech is one very intriguing development. Here, AI predictions are put to the test in actual laboratories, and the outcomes are instantly fed back into algorithms. This circular learning process is very effective because it enables the system to improve itself and reach a level of precision that was previously only possible through intuition. The idea that biology learns from machines and machines learn from biology is almost lyrical.

There is a clear human component to this endeavor that goes beyond technology and financial gain. Every dataset has a backstory—a patient, a family, a life upended by illness. These businesses are driven by very personal motivations. First-hand encounters with sickness drew several innovators, including Gibson, to biotechnology. This competition has a moral significance that goes much beyond quarterly profits because of its shared emotional bond.

These developments could have a profound effect on society. By identifying abnormalities in mammograms and CT images with remarkably comparable accuracy to human experts, AI-powered screening systems are already demonstrating promise in the early diagnosis of cancer. By detecting tumors long before they spread, this could save many lives. Additionally, AI models are demonstrating remarkable clarity in the classification of tumor subtypes, enabling oncologists to make more confident treatment decisions.

However, there are obstacles in the race that go beyond math. In order to assess medications that are partially designed by machines, regulatory bodies must adjust. Patient privacy, transparency, and data ownership are becoming more and more ethical issues. No matter how revolutionary the technology is, businesses must make sure it stays responsible. Another risk is overconfidence, which occurs when algorithmic efficiency is mistaken for infallibility. These models still rely heavily on human oversight.

The trajectory is promising in spite of these difficulties. Every experiment advances the medical community’s knowledge of how illnesses manifest and how to treat them. The goal of the convergence of AI and medicine is to enhance scientists rather than replace them by optimizing processes and freeing up human talent for empathy and innovation. The intuition is still incredibly human, but the machines are the muscle.