Pancreatic cancer has long been treated like a sealed vault—impenetrable, relentless, and terminal. Doctors, patients, and even researchers have learnt to discuss it with grave caution. But at the age of 74, Mariano Barbacid is exhibiting something astonishingly effective: patience accompanied by accuracy may finally give a key.

Barbacid gained notoriety in 1982 after identifying the HRAS oncogene. That one discovery influenced doctors’ understanding of cancer as a profoundly genetic disorder rather than a strange ailment. His findings pushed researchers to map the language of each tumor before attempting to treat them all in the same way.

After returning from the United States to lead cancer research in Spain, Barbacid developed a lab focused less on rapid results and more on patient strategy. For decades, that lab hammered away at one of cancer’s most intractable opponents—pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma.

This form of cancer is infamously quick, frequently detected late, and resilient to almost all that is thrown at it. Treatments that work on other malignancies seem to stall here. Tumors are momentarily reduced by new medications, but resistance recurs automatically. It’s a vicious pattern.

| Item | Detail |

|---|---|

| Name | Mariano Barbacid |

| Born | 4 October 1949, Madrid, Spain |

| Field | Molecular oncology, cancer genetics |

| Known For | Discovery of the first human oncogene (HRAS); KRAS research |

| Institution | Spanish National Cancer Research Centre (CNIO) |

| Recent Milestone | Complete elimination of pancreatic tumors in mouse models |

| Reference | https://www.pnas.org |

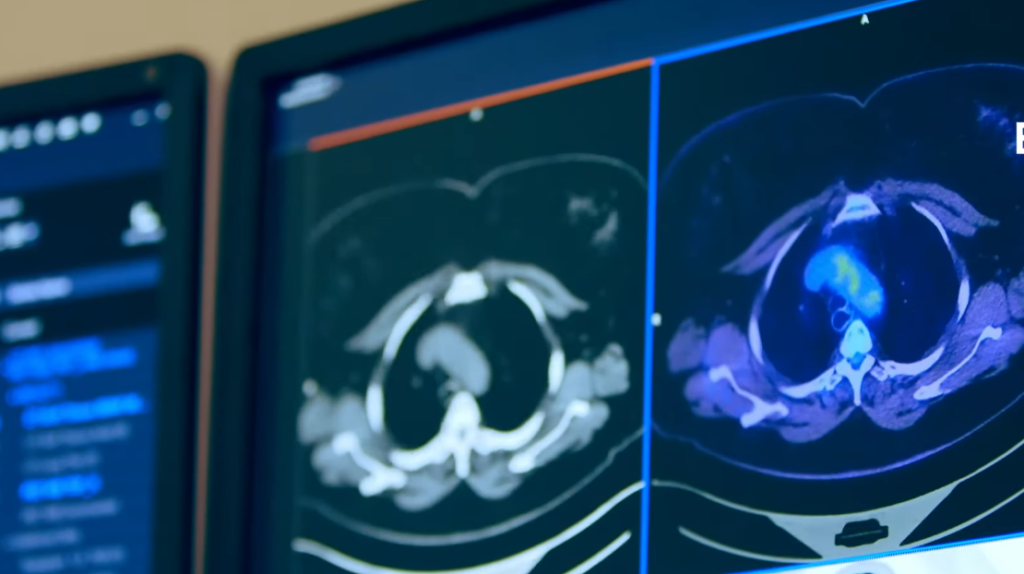

Barbacid’s team tackled the issue like engineers deconstructing a bridge rather than depending on a single, forceful blow. They found three structural supports in the cancer’s signaling pathway—KRAS, EGFR, and STAT3—and decided to block all of them at once.

The outcome in mice models was not just promising, but astounding. The tumors became smaller until they disappeared completely. Months passed. No recurrence occurred. The mice, remarkably, accepted the treatment without major side effects. It was an extraordinarily harmonic mix of strength and restraint.

The treatment stopped the tumor from taking a detour by focusing on several places in the signaling chain. It left no alternate avenue for regrowth. This multifaceted shutdown approach was very creative because it avoided the cancer’s typical evasiveness.

Crucially, Barbacid has been slow to declare this a human remedy. His tone remains extraordinarily clear: mouse models are not people. The next stage—adapting this for human trials—will involve meticulous changes, recalibrated doses, and a long view. However, he has demonstrated that resistance may no longer be unavoidable.

The therapy utilized here isn’t a hidden weapon, but a dance of recognized agents acting together. That orchestration makes it very versatile, perhaps transferable to other malignancies with comparable pathways. Its simplicity may even work to its advantage.

Not only is the scientific outcome noteworthy, but so is the underlying attitude. Barbacid’s crew put endurance before spectacle, rejected gimmicks, and refused to take short routes. This strategy is remarkably similar to craftsmanship at a time when research headlines are frequently dominated by rapid wins.

The wider implications are subtly revolutionary. Pancreatic cancer has resisted advancements for many years. Even new targeted medications have delivered only short prolongation of life, frequently with considerable toxicity. This new approach modifies the script; at least in preclinical trials, it eliminates the threat rather than temporarily extending life.

The results’ longevity was especially advantageous. There was no covert reappearance months following treatment. Not only were the tumors latent, but they had completely disappeared. This type of outcome redefines what can happen when several vulnerabilities are exploited at once.

The study also highlights how far research tools have come. Genetically engineered mouse models and molecular profiling are now sophisticated enough to guide treatments like these with astounding accuracy. These improvements have considerably decreased the guesswork that often shrouded early-stage oncology.

Barbacid has experienced his share of failure. That viewpoint influenced his prudence. However, his optimism now seems justified rather than overblown. He is merely demonstrating, with solid evidence, that one of medicine’s most tenacious enemies may finally be losing ground. He is not making any claims about miracles.

By purposefully avoiding arrogance, Barbacid establishes credibility. His lab is focused, his methods are grounded, and the research speaks louder than any press release. It’s a reminder that progress doesn’t always declare itself with fanfare—it sometimes arrives slowly, under the radar, prepared to last.

For patients and professionals, hope tends to come with caveats. This time, however, the evidence is not just encouraging but also remarkably stable. That kind of result doesn’t just turn heads; it reorients long-held assumptions.

Barbacid’s legacy gets sharper when clinical trials are planned and financing is obtained. He created pathways rather than chasing headlines. And today, those routes are closing doors on cancer cells that once refused to go.

This most recent study provides direction rather than just data through deliberate perseverance and smart targeting. And that’s a remarkably resilient form of advancement for a malignancy that previously provided none.