Although people have long been fascinated by space travel, it has a particularly powerful influence on young scientists, helping to mold their goals. For young learners, the excitement of exploration, the quiet immensity beyond Earth, and the pursuit of unachievable goals come together to create something especially motivating. By transforming curiosity into a purpose, astronauts like Dr. Roberta Bondar, Chris Hadfield, and Mae Jemison continue to personalize science.

Organizations like NASA and the Canadian Space Agency have significantly enhanced the way that youth view science through educational initiatives and interactive missions. These programs inspire rather than merely instruct. An astronaut floating above Earth while describing gravity ignites a flame in students that textbooks seldom do. It is both lyrical and incredibly inspiring to think that knowledge may practically lift you off the ground.

NASA’s initiatives demonstrate that exploration is not limited to rockets and telescopes. By allowing students to participate in research via the International Space Station, it provides a very effective setting for encouraging practical experience. For instance, students can create tiny satellites that orbit the Earth through CubeSat missions. This experience turns abstract physics into observable outcomes by bridging theory and reality in a way that feels remarkably apparent.

| Person | Dr. Roberta Bondar |

|---|---|

| Profession | Astronaut, Researcher, Physician |

| Nationality | Canadian |

| Known For | First Canadian woman in space; influential STEM role model |

| Key Mission | Space Shuttle Discovery (1992) |

| Scientific Focus | Neurology, space medicine, environmental research |

| Influence on Youth | Inspires global STEM outreach and education programs |

| Verified Reference | NASA: https://www.nasa.gov |

The importance of representation is also recognized by the Canadian Space Agency. Many young Canadians, like current astronaut Jenni Gibbons, were inspired by Dr. Roberta Bondar’s voyage on the Space Shuttle Discovery. Gibbons frequently attributes her belief that space was accessible to Bondar’s example. These narratives are especially helpful because they humanize scientific achievement, making it less about brilliance and more about tenacity and a sense of shared awe.

Through initiatives like CUBICS and STRATOS, students have been able to construct and launch tiny satellites, creating equipment for atmospheric research. These are especially creative experiences that give participants a look at actual aerospace problems. These initiatives work with schools to establish ecosystems where learning is no longer theoretical but rather active. The experience, according to many students, is life-changing and permanently shifts their goals toward science and exploration.

Above us, the International Space Station functions as a living classroom. It has supported investigations that link biology, chemistry, and engineering for more than 20 years. Students who follow these missions discover how international collaboration fosters innovation. The ISS has developed into a very flexible teaching tool that connects teachers and students with a common goal and opportunity.

Outreach to astronauts is now a crucial component of this cycle of inspiration. The impact of astronauts visiting schools, whether in person or by live video from orbit, is electrifying. As they hear about lunar training or microgravity experiments, children lean closer, their eyes expanding with anticipation. These instances give science a concrete, approachable, and even sentimental quality. It is narrative at its most potent; it is more than just education.

Space exploration, according to Bill Nye, is humanity’s greatest investment in curiosity. Young people today, who frequently want purpose and influence in their professional endeavors, find great resonance in that viewpoint. They start to recognize the extraordinarily broad range of options that science offers, from robotics to planetary defense, from health to climate research, by viewing scientists as explorers and problem-solvers rather than solitary academics.

Powerful teaching tools are recent missions like NASA’s DART project, which investigated the feasibility of changing an asteroid’s trajectory. They demonstrate that exploration encompasses invention and protection in addition to discovery. This insight can change the lives of young people who are enthralled with bravery and meaning. They view science as humanity’s most useful kind of bravery rather than as a far-off theory.

This inspiration is further enhanced by cultural influence. Through his guitar performances on the ISS, Chris Hadfield reached millions of people on social media, fusing science and art in a way that felt remarkably similar to how creativity and innovation coexist in any great invention. Even those who have never considered becoming scientists find space missions fascinating because of the link between human expression and scientific pursuits. It proves that everyone has the right to explore.

These missions have also served as inspiration for the music, fashion, and film industries. The Artemis program’s focus on sustainability and diversity has been incorporated into video games, song lyrics, and art displays. When young people see these cultural resonances, they feel a part of something greater, something that combines creativity and purpose. This blending of creativity and science is incredibly successful in maintaining public interest over time.

Another source of inspiration for these initiatives is international collaboration. The ISS, which is run by several space agencies, is evidence that science flourishes when boundaries are blurred. Students who watch these collaborations discover that collaboration is necessary for the most ambitious goals. In today’s divided world, where teamwork feels both necessary and hopeful, this lesson—which is taught through orbiting laboratories rather than lectures—is especially helpful.

Initiatives of any size can have a huge impact. A student’s path can be altered by a single NASA-sponsored classroom experiment or a local science fair related to the Mars Rover mission. When talking about propulsion systems or space habitats, teachers frequently describe how students who previously had attention problems became intensely focused. It seems as though a core human desire to discover, create, and comprehend is awoken by curiosity.

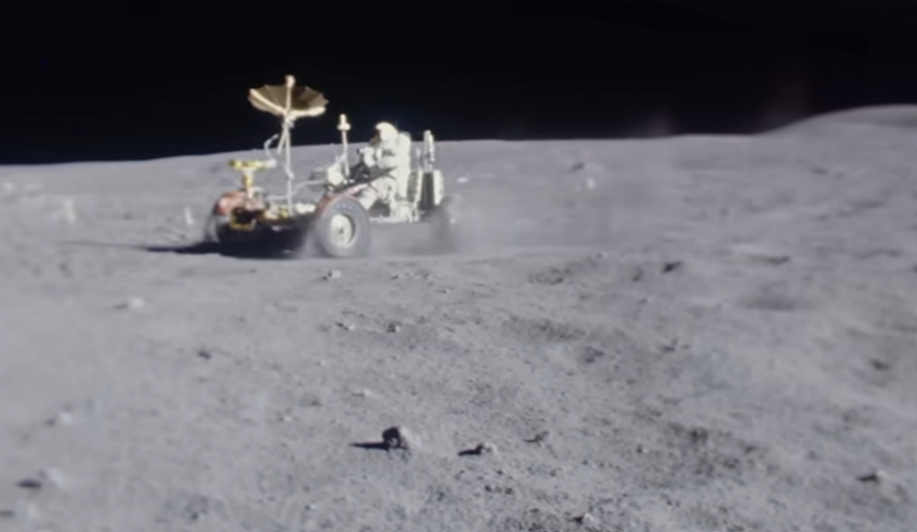

Today’s labs and companies are led by many people who grew up seeing the Moon landings or Space Shuttle launches. Their professions are a reflection of a tradition of inspiration that has shown itself to be incredibly dependable over many years. We developed a persistent culture of curiosity as a result of space exploration, in addition to new technologies. Every young student who poses a question that starts with “what if?” contributes to the continued growth of that culture.

These initiatives shift the focus of science from memorization to engagement. It’s not perfection but discovery that brings the joy. The moment becomes indelibly ingrained in a student’s mind when they witness their satellite broadcast data or observe a robot imitating human movement in microgravity. They begin to view school as life itself—constantly changing, demanding, and incredibly fulfilling—rather than as a means of preparing for it.

Space exploration has a subtle but significant impact on our collective imagination. Every successful mission, every orbital photo of Earth, and every astronaut’s tale changes the way we perceive what is possible. And that feeling of possibilities is translated into action in classrooms across continents—new concepts, novel experiments, and professions characterized by curiosity.