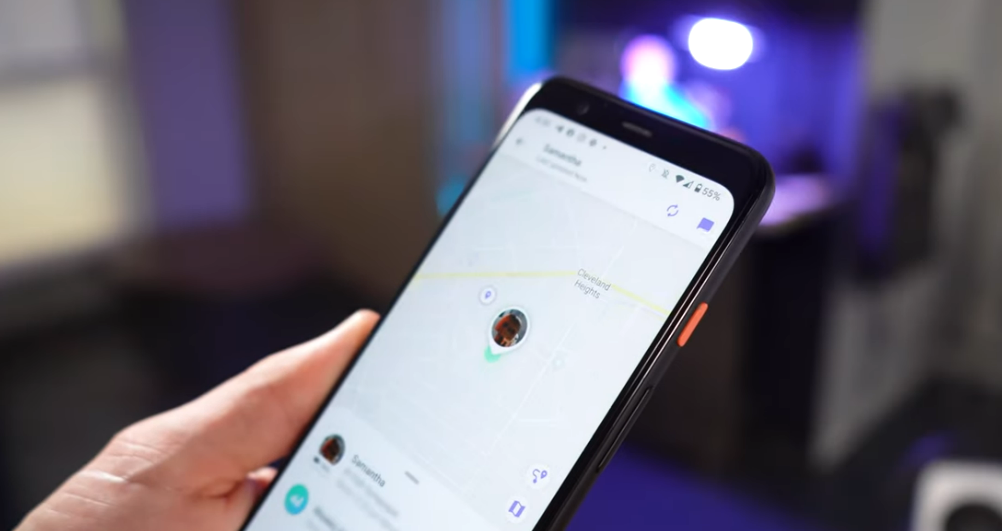

Life360 was created with the intention of making families feel safer, but its legal issues have twisted that pledge into a troubling discussion about responsibility, privacy, and the hidden costs of technology. The current cases involving the app go beyond commercial tactics; they call into question the definition of “safety” in a time where connectivity is paramount.

The business, which is well-known for its slick user interface and family-friendly advertising, is presently dealing with three significant legal issues. Despite their notable differences, they all center on the same idea: how personal vulnerability may be transformed into digital convenience.

In the first complaint, GoCodes Inc. is suing Life360 for allegedly violating its proprietary location-sharing technology. According to GoCodes, Life360’s primary tracking feature duplicates a technology that it previously obtained intellectual property protection for. In Silicon Valley, where innovation frequently outpaces regulation, such assertions are especially prevalent. However, this argument demonstrates how quickly changing concepts can make it difficult to distinguish between imitation and inspiration.

The second case that has sparked the most public indignation is a class-action lawsuit brought by stalker victims. The plaintiffs allege carelessness and flawed design on the part of Life360, its subsidiary Tile, and Amazon. They contend that although the app’s technology was designed to protect families, stalkers have abused it, frequently with disastrous emotional results. According to the complaint, these hazards were predictable and ought to have been handled long before any harm was done.

Life360 Company Overview

| Category | Details |

|---|---|

| Company Name | Life360, Inc. |

| Headquarters | San Mateo, California, United States |

| Founded | April 17, 2007 |

| Founders | Chris Hulls, Alex Haro |

| CEO | Chris Hulls |

| Public Listing | Australian Securities Exchange (ASX: 360) |

| Main Product | Life360 App – Location and Family Tracking |

| Users | Over 48 million monthly active users (as of 2022) |

| Subsidiaries | Tile (acquired 2021), ZenScreen |

| Revenue | Approx. $228.3 million (2022) |

| Legal Issues | Privacy, data-sharing, stalking negligence, patent infringement |

| Official Site | life360.com |

Even online conversations in which people described employing trackers for predatory reasons are cited in court filings. The claims are especially unsettling since they imply that the business may have unintentionally promoted abuse through its marketing strategies. The plaintiffs describe a tech-optimistic culture that, despite its profitability, failed to protect against safety flaws.

Allstate Corporation and its data analytics division, Arity, are the focus of the third lawsuit, which was brought by Texas Attorney General Ken Paxton. According to the complaint, users’ driving information was surreptitiously gathered and sold to insurance firms by Life360’s embedded software. Allegedly, this information—which included behavioral analytics, speed, and exact location—was used to support premium hikes without getting user approval. The issue is remarkably comparable to other scandals that have changed the public discourse on digital ethics.

The conflict between technology and transparency is brought into stark relief by this instance. Once viewed as a useful family tool, Life360’s software today represents how personal information can be turned into corporate currency.

These lawsuits are especially significant because they all point to the same unsettling reality: the reliability of the system overseeing digital safety depends on it. Ironically, families have been exposed to threats they never expected from the technology that was supposed to safeguard them.

These charges go right to the core of Life360’s brand, according to CEO Chris Hulls, who founded the business on ideas of compassion and connection. Hulls has frequently been vocal on social media, responding directly to teenagers who object to the app’s continuous tracking. His implementation of the “Bubbles” feature, which momentarily obscures specific location data, was perceived as a show of consideration for users who are concerned about their privacy. Even though the cases now test whether goodwill can overcome systematic problems, it was astonishingly successful in softening the brand’s image.

Analysts compare the situation at Life360 to the impact from Cambridge Analytica at Meta. Both show how businesses that are based on connections eventually have to deal with the ethics of control. They also point out that the public’s tolerance for data abuse has significantly decreased. Today’s consumers are far more aware of the compromises between surveillance and safety.

A societal change is also reflected in the Life360 lawsuits: a rising mistrust of the “always-on” manner of living. Families that were formerly comforted by being able to track one another’s whereabouts are now wondering if this level of intimacy crosses the line into invasion. According to psychologists, hyper-tracking can erode trust, especially between parents and teenagers. Care can turn into digital dependence, when privacy is seen as a privilege rather than a right.

Supporters contend that Life360 has achieved notable progress in accountability in spite of these issues. According to the corporation, user consent is given priority, encryption standards have been strengthened, and third-party data sharing has been restricted. The lawsuits, according to some defenders, are an inevitable test of a developing technological industry that grows from its mistakes rather than crumbles.

However, the wider ramifications go beyond just one app. For example, the Texas data-privacy lawsuit may become a seminal case in the enforcement of state-level data protection. If it is successful, it might provide new legal guidelines for the gathering, use, and disclosure of consumer data. This change may put pressure on computer firms throughout the country to implement more stringent compliance policies.