AI is no longer solely a subject for Silicon Valley think tanks and college labs. Lesson planning, student assignments, and classroom procedures are all subtly incorporating it. Education professionals are increasingly calling for the formalization of artificial intelligence education through national literacy standards that address ethics, logic, and social impact in addition to tool training. However, there is no agreement on who should spearhead the effort, despite widespread recognition of the significance of AI.

The movement to standardize AI education has accelerated in the last 12 months. With bipartisan backing, Congress passed the Artificial Intelligence Literacy Act in 2024 with the goal of commissioning a national framework and funding trial programs. Globally, the OECD said that AI literacy would be evaluated alongside reading, arithmetic, and science in its 2029 PISA test for 15-year-olds. Additionally, the European Commission is developing an AI Literacy Framework specifically for younger learners. However, many teachers in schools themselves are navigating this change without a road plan.

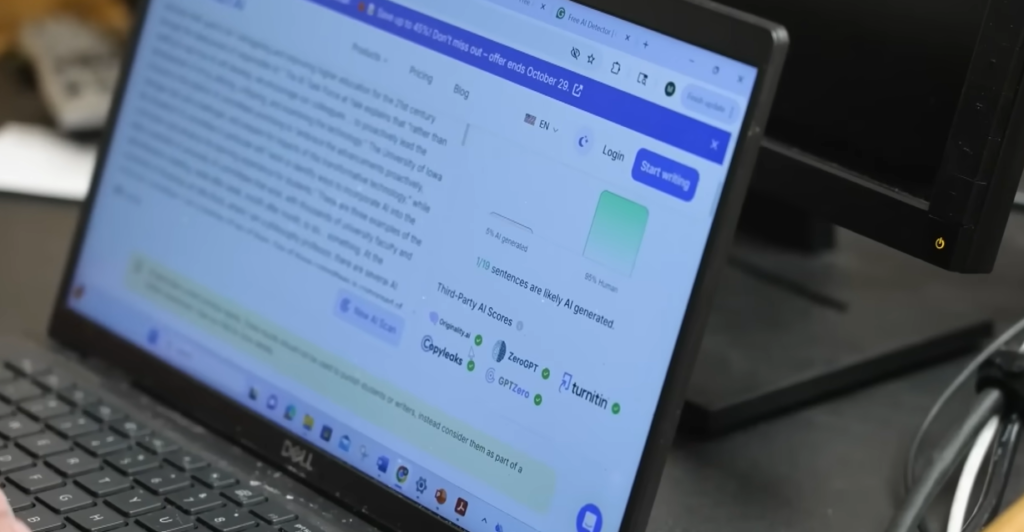

A gap is emerging between the policy’s speed and classroom preparedness. Approximately 60% of American educators employed AI techniques in the 2024–2025 academic year, according to Gallup and Turnitin. Despite this quick adoption, almost half acknowledged that they felt unprepared to instruct pupils in the responsible use of these tools. Additionally, according to Turnitin, 95% of administrators think AI is being abused in classrooms, but few have concrete plans to stop it. Teachers are experimenting on their own, frequently without professional development or organized assistance.

Key Context on AI Literacy Standards in Education

| Topic | Details |

|---|---|

| Issue at Hand | National push for standardized AI literacy education in K–12 and beyond |

| Driving Forces | Tech integration in classrooms, AI’s societal impact, federal interest |

| Notable Legislative Action | “Artificial Intelligence Literacy Act” (2024), bipartisan backing |

| Global Developments | OECD’s 2029 AI literacy assessment (via PISA), EU AI Literacy Framework |

| Concerns Raised | Commercial influence, ethical ambiguity, teacher readiness |

| Leading Advocates | Susan Gonzales (AIandYou), Leo Lo (University of New Mexico) |

| Resistance & Caution | Academic critique, overstandardization, marginalization of educators |

| Current Adoption Rate (U.S. K–12) | 60% of teachers used AI tools in 2024–2025 |

Susan Gonzales, a former teacher and current CEO of AIandYou, is aware of the risks. Her group has worked to make AI literacy more accessible, particularly to groups that have traditionally been left out of discussions about technology. She frequently stresses that AI literacy is about demystifying the systems that increasingly influence our digital lives, not only about knowing how to code or use chatbots. Even yet, she admits that fear and unfamiliarity continue to be significant barriers. In a recent address, she said, “We can’t teach what we don’t fully understand ourselves.”

Teachers who feel excluded from national discussions strongly identify with that worry. Particularly outspoken researchers like Susan Lee Robertson and J-C Couture have criticized existing frameworks for being unduly corporate and philosophically ambiguous. Their investigation showed that the very documents meant to direct their classrooms hardly referenced teachers. Rather, private IT companies like Amazon Web Services, Microsoft, and OpenAI have a major influence on legislation. Additionally, these businesses serve on advisory boards for organizations like TeachAI, which raises questions about prejudice and covert business interests.

Critics contend that by putting businesses at the forefront of curriculum development, we run the risk of transforming AI literacy from a pedagogical endeavor to a brand exercise. Classrooms are already experiencing that stress. In order to avoid the hazy boundary between plagiarism and AI support, some districts are reverting to handwritten assignments, while others are embracing AI through writing aids and detection tools.

However, educators are attempting to innovate rather than merely respond. Teachers are creating their own methods for teaching AI literacy, especially in high schools. For instance, one English teacher in Ohio allows pupils to examine the distinctions between poetry written by humans and by machines using generative technologies such as ChatGPT. In a different media literacy class in California, students created fake news using AI and then disproved it. These practical lessons show that teachers can be extremely creative in leveraging AI as a platform for greater learning when they are trusted.

However, many people lack safeguards due to the lack of a national framework. AI literacy devolves into a patchwork of individual experiments in the absence of agreed-upon definitions or specific goals. Even worse, it turns into a reflection of current injustices. Tech-savvy staff and schools with access to technology lead the way, while others lag behind. Susan Gonzales said, “If AI literacy becomes a privilege, we’ve failed,” warning of a growing divide.

The definition of literacy itself is also at risk. Is it only about making good use of tools, or should it also involve being able to analyze and challenge them? A relevant norm, according to academics, must incorporate ethical reasoning, a knowledge of algorithmic bias, and a grasp of how AI influences decision-making in a variety of domains, including hiring and healthcare. In the absence of those components, students may learn how to provoke a chatbot but not how to question its responses.

The 2029 launch of the OECD’s PISA test might compel a reckoning. AI literacy will become significant once it can be measured. Schools can be evaluated using metrics they hardly comprehend. More districts may be compelled by this pressure to implement hasty fixes, frequently under the direction of suppliers selling pre-made “AI literacy kits.” However, profound comprehension rarely results from fast remedies. They frequently substitute checkbox compliance for sincere inquiry.

For this reason, many educators are advocating for a more deliberate, slower approach. They desire national norms, but they should be the result of discussion rather than order. They seek frameworks that address AI as a civic issue rather than merely as a skill. Additionally, they encourage pupils to use AI tools as they grow up and consider their ramifications.

There is cause for optimism. Teachers, researchers, legislators, and parents are having significantly more nuanced discussions now than they did a few years ago. Better questions are being asked. They are focusing more intently. Additionally, students are realizing that AI literacy is about agency rather than just robots.

We might not just create better AI users if that spirit informs future standards. We could help create more intelligent citizens. After all, the real test of every educational endeavor is not just what students are capable of, but also how carefully they choose to accomplish it.