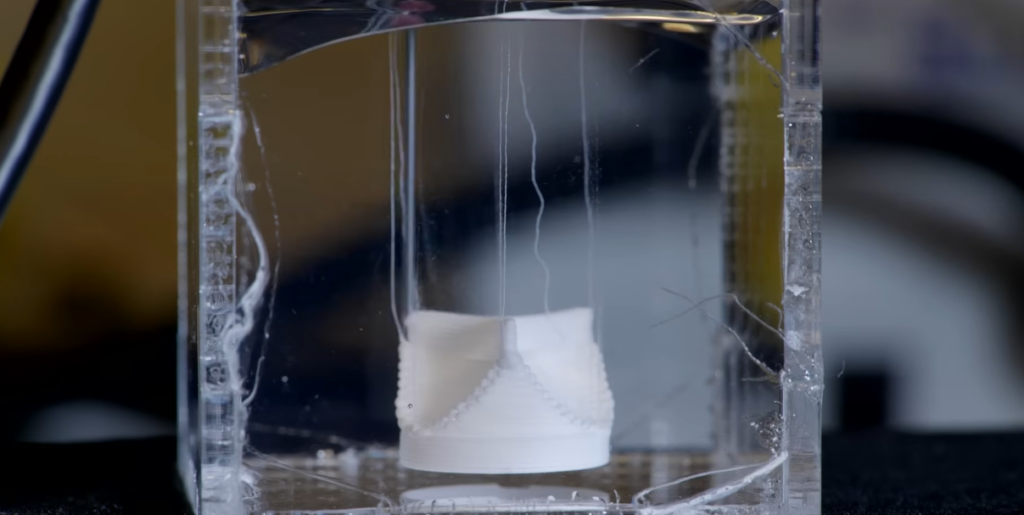

The item being printed initially appears to be a soft-serve swirl. It forms cell by cell while resting silently on a chilled platform. This patch of living tissue, however, is not dessert or décor; rather, it is the result of a technique that is both incredibly successful and profoundly transformative: 3D bioprinting.

Scientists are creating tissues that can replicate the body’s own by fusing digital engineering and biology. The promise of printing using living cells has evolved over the last ten years from future fantasy to real-world use. These tissues breathe, beat, and perform functions; they are not merely theoretical models.

This is where bioinks come in. These specifically created materials mimic the soft, flexible milieu of the human body by suspending live cells in hydrogels or polymers. Because of their extreme versatility, researchers can modify their formulations to print cartilage, muscle, or even neural tissue.

Extrusion-based printing uses a nozzle to deposit bioink layer by layer, much like piping frosting. Every pass preserves cell viability while simultaneously constructing structure, which is very challenging to do reliably. Skin and other thinner tissues go through the process much more quickly and easily. The endeavor becomes considerably more complicated for more vascularized, denser organs like the heart or kidneys.

| Key Detail | Description |

|---|---|

| Technology | 3D bioprinting with living cells and bioinks |

| Core Material | Bioink (blend of live cells and biomaterials like hydrogels) |

| Methods | Extrusion, inkjet, and laser-assisted printing |

| Primary Use | Tissue engineering, organ replacement, drug testing |

| Bioink Features | Biocompatible, shear-thinning, printable at low temperatures |

| Key Challenge | Vascularization and long-term tissue integration |

| Emerging Trend | 4D bioprinting: time-responsive structures for dynamic tissue behavior |

| Real-World Impact | Potential to eliminate donor waitlists and personalize medicine |

I observed a technician calibrating a triple-extrusion printer while standing behind a curved glass window one afternoon in San Diego. She treated the bioink cartridges as if they were eggs. There were three distinct cell types in each chamber: smooth muscle, endothelium, and epithelial. As a result, a simple artery segment was carefully and precisely printed. Although it was not intended for implantation, there was no denying its potential.

This type of technology is especially helpful in the context of healthcare shortages, especially with regard to organ transplantation. Every year, many pass away while awaiting a suitable donor. In the future, bioprinting may allow patients to obtain customized tissue made from their own cells, which would lower the possibility of rejection and greatly enhance the results of surgery.

However, there are still problems that need to be fixed. Cells deep within thicker tissues struggle to survive in the absence of a circulatory network. Some researchers are simulating capillaries with integrated oxygen channels, while others have experimented with sacrificial materials that disintegrate to create hollow vessels. Although full-organ viability is still a challenge, these tactics have significantly increased cell lifetime.

Another route is provided by laser-assisted printing. It makes it possible to carefully construct complex structures by precisely placing cells. However, it might cause thermal stress, necessitating careful calibration and cooling. Inkjet printing, on the other hand, is more delicate but has a smaller range of tissue types and densities.

The advancement has been fairly quick in spite of these trade-offs. Recently, chemotherapeutic medications have been tested using tissue models created from patient-derived cells. As a morally sound and effective substitute for animal research, pharmaceutical companies are embracing this. Known as organoids, these little organs provide insights into human biology that were previously unattainable through such precise and large-scale observation.

Some laboratories have started anticipating the best print parameters based on tissue type by utilizing machine learning. These prediction models have accelerated experimentation durations by drastically reducing trial-and-error cycles. This breakthrough is especially novel for medium-sized research labs with tight finances, as it eliminates obstacles that hindered progress in the past.

Additionally, a change in philosophy is occurring. Many organizations changed their focus during the epidemic to resilience, emphasizing decentralized healthcare and flexible solutions. Because it is very efficient, scalable, and local, bioprinting aligns with that philosophy. Consider a facility in Nairobi that produces trachea stents for kids without the need for foreign implants.

Companies like Organovo, Prellis, and CELLINK are integrating AI for tissue analysis, expanding operations, and improving the composition of their bioinks through strategic collaborations. In an attempt to better connect with human systems, several businesses are working with live inks that change over time, which might lead to 4D bioprinting.

Bioinks are living, reactive, and temperamental, much like sourdough starting, according to an engineer I spoke with. Errors in the recipe will result in nothing forming. However, it is alive in every way when it functions. That analogy stuck in my mind.

Regulatory frameworks will need to change in the years to come. Test-produced tissue is one thing, but tissue that is implanted into a human being needs to be closely monitored at every stage. From function to sterility, from cell sourcing to biodegradability, the criteria need to be very explicit and universal.

Some research teams are now recording each cell batch, ink composition, and print layer by incorporating blockchain technology. When tissue activity could mean the difference between life and death, reproducibility is essential, and this digital trail guarantees it. For auditing purposes, these technologies are also very dependable and provide transparency without sacrificing intellectual property.

National research centers have seen a nearly 40% rise in funding since the start of various public-private bioprinting programs. Governments are starting to view these initiatives as part of a larger bioeconomy strategy, where printed organs and tissues might lower healthcare costs and increase life expectancy, rather than as niche endeavors.

It is not science fiction that all hospitals will have bioprinters in the future. It’s a quantifiable strategy supported by progress. 3D bioprinting is revolutionizing not only patient care but also the way we envision creating the human body by fusing biological expertise with engineering accuracy.