The photo appeared strangely familiar at first glance, hazy at the edges, as if fading from memory, like a long-lost relative of European royalty. It was hanging at a gallery in New York, looking out serenely from a gilded frame without raising any red flags. Then viewers saw the signature—a mathematical formula instead of a name.

The French art collective Obvious trained an AI to create the sculpture, which was named Edmond de Belamy. It shocked the art world when it was sold at Christie’s for $432,500 in 2018. Experts were astounded not only by the cost but also by the fact that they had no idea it wasn’t painted by a human. Unaware that they were reacting to something derived from lines of code, they had evaluated it based on technique, intuition, and emotion.

It was more than just its digital origin that made this unique. The presence of the portrait was serene, eerie, and somehow recognizable. It delicately distorted expectations while reflecting the tenderness of oil portraits from the 18th century. Thousands of old paintings were used to train the AI. Without ever comprehending either, it created something incredibly powerful at arousing emotion and memories through the analysis of patterns and aesthetics.

This was no trick or filter. It was the outcome of a GAN, in which one neural network produced the images and another continuously evaluated them. Even seasoned curators were persuaded by the artwork’s refinement, which was analogous to two competing artists locked in constant feedback. It was this tension between invention and criticism that resulted in something that was both technically good and emotionally compelling.

Key Context Table

| Element | Detail |

|---|---|

| AI Technique Used | Generative Adversarial Network (GAN) |

| Notable Work | Edmond de Belamy by French collective Obvious |

| Year of Recognition | 2018, auctioned at Christie’s for $432,500 |

| Public Reaction | Debates over authorship, creativity, and the definition of “art” |

| Expert Confusion | Many rated the AI-generated works as more “inspiring” than human-made |

| Technology Origin | GAN developed by Ian Goodfellow in 2014 |

One curator I talked to at an exhibition preview thought the painting was a contemporary homage to neoclassicism. She paused after complimenting the brushwork. She said, “It’s a little unsettling, but it’s… moving.” She didn’t know it wasn’t made by humans until much later.

The emergence of AI art in recent years has brought up both important and unsettling issues. Does the fact that something can evoke feelings in us even though it was created by a machine negate those feelings? Is it possible for beauty to exist without purpose? These discussions are no longer theoretical. They are now appearing in marketplaces, museums, and galleries.

People frequently give AI-generated art better ratings when they are unaware that the creator is a machine, according to an intriguing 2017 study from Rutgers University. When we call it human, depth and brilliance become apparent. If you call it fake, admiration wanes. The way people respond to music when they learn it was created by an algorithm rather than a band is quite comparable to that change.

This cognitive bias affects trust as much as genuineness. We’ve been taught that human experience is necessary for feeling. However, Edmond de Belamy’s AI utterly refuted that story by creating something that had a remarkable capacity to evoke meaning and memory.

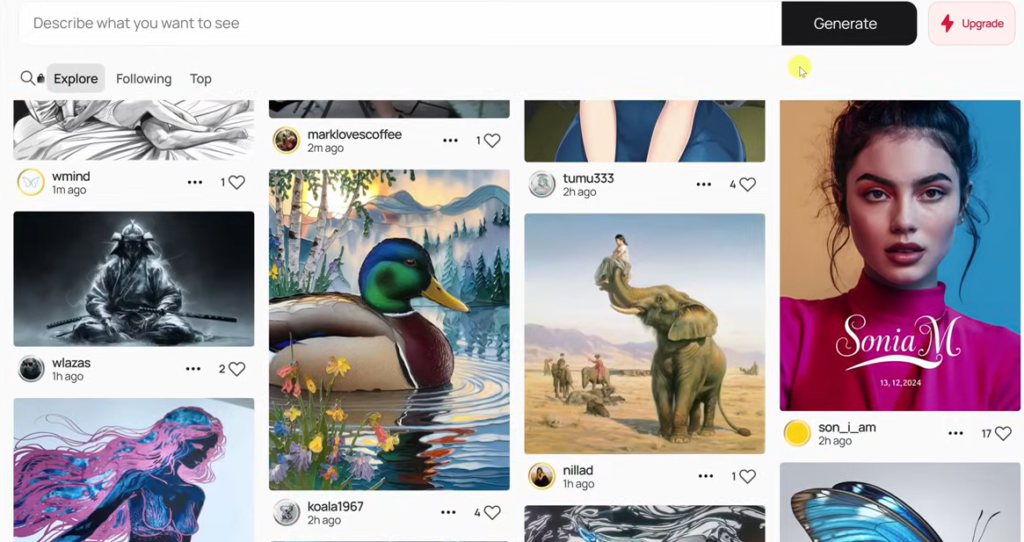

There are differences among artists. While some see AI as a help, others see it as a threat. However, its existence cannot be denied. Creators can now create intricate and visually stunning graphics in a matter of minutes thanks to platforms like Midjourney and DALL·E. A rising number of these outputs have begun to mix in seamlessly with traditional aesthetics, even though many are obviously machine-made. The distance is getting smaller.

Creatives are no longer merely employing algorithms; they are now working with them through purposeful experimentation. They are co-authoring works that blur the boundaries between purpose and interpretation by providing AI systems with voice commands or handwritten sketches. When done well, that approach feels very adaptable.

In contrast to Photoshop, which needs expertise and guidance, generative AI works like an inquisitive apprentice. It provides options you didn’t request. It occasionally provides something better than you had anticipated. Artistic workflows have changed as a result of that change, significantly increasing in breadth and speed. The outcome is redefinition rather than replacement.

Nevertheless, modern technology compels us to reconsider the boundaries of art. What’s left if we take away the artist’s intention? The audience may have the key to the solution rather than the author. Meaning, after all, has always been a collective experience. Even when they weren’t intentionally placed there, we might discover tales in forms and feelings in colors.

One of the most controversial statements in modern art is Edmond de Belamy’s signature, which is a series of mathematical arguments. It tells a different type of story—one that is framed by human curiosity, authored by pattern recognition, and honed by probability—not because it doesn’t have a name.

There will probably be more pieces of art that cross these lines in the years to come. Creations, not replicas. Invention, not imitation. As models develop, they’ll start creating previously unseen aesthetics—styles that come from synthesis rather than memorization. Some might be amazing, while others might be strange. However, since we trained the machines to perceive beauty in the same manner that people do, they will all somehow reflect us.