At the Osaka Expo, a man stood coolly in the heat, a neck fan buzzing softly next to his chin, powered by his vest. Ultra-thin solar films were concealed inside the cloth, almost weightless and scarcely perceptible; they were so subtle that they could have been mistaken for lining. But don’t misunderstand—these movies represent a developing change in the way we produce and transport energy.

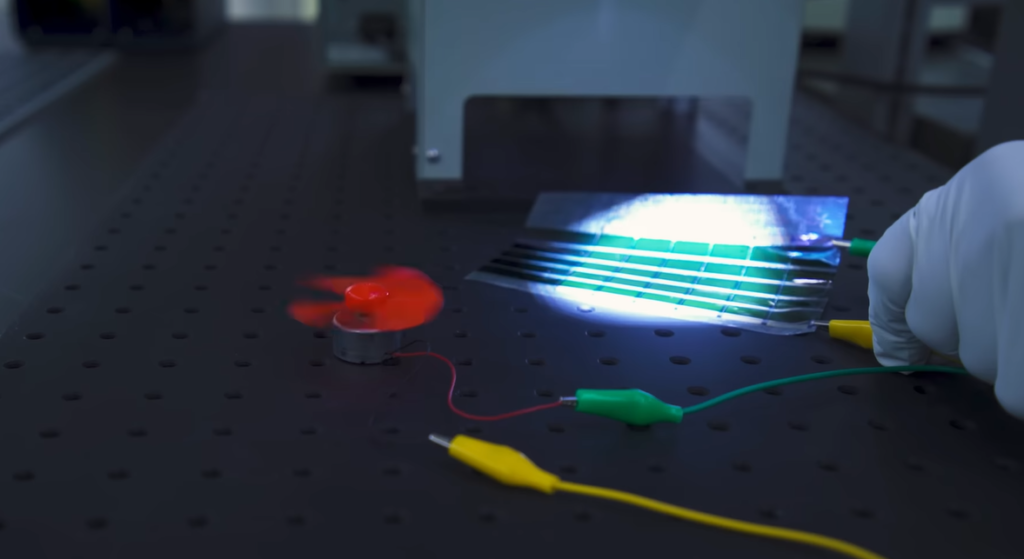

These solar sheets are made of minerals known as perovskites. Even while that might sound like something from a textbook on chemistry, their talents are remarkably similar. Even as clouds roll in, they absorb sunshine. They don’t have to be mounted or rigid. Additionally, they are adaptable enough to be printed onto a bag or stacked into a tent.

What’s driving this next solar phase is that kind of independence. Most people are aware that solar panels are hefty, flat, and fixed. They are almost ineffective for moving bodies or street infrastructure, yet they work flawlessly on rooftops. Perovskite-based films, on the other hand, have a distinct personality; they fold with fabric, flex with motion, and remain functional under pressure. They are more than panels. Potential exists in them.

Expo 2025 made this possibility a reality. Solar layers were integrated onto staff uniforms to power cooling fans and charge mobile devices. Perovskite films wrapped over the structure of smart poles in the exposition grounds provided illumination. It was the same source that bus terminals tapped. It was not a futuristic atmosphere. Quietly, it was up to date.

| Key Detail | Description |

|---|---|

| Technology | Ultra-thin perovskite solar cells (thinner than a human hair) |

| Key Features | Lightweight, flexible, printable, low-light efficiency |

| Efficiency | Up to 21.2% lab-tested conversion; effective even in cloud or shade |

| Wearable Integration | Clothing, vests, neck fans, backpacks, tents, drones, buildings |

| Real-World Demo | Expo 2025 Osaka: Solar-powered staff vests, smart poles, bus terminals |

| Lead Challenge | Lead content in perovskites; minimized by advanced encapsulation |

| Longevity Challenge | Perovskites degrade faster than silicon without protective layering |

| Outlook | Commercial use emerging, especially in hybrid tandem panels |

These gadgets are quite similar to commonplace items, in contrast to previous wearable solar efforts that frequently felt like novelty gear. That is deliberate. Instead than standing out, developers want the technology to blend in. Furthermore, the cells are distributing in multiple environments this time. They are working indoors, even at dusk, and under cloud cover.

When used, they are almost detectable and are very good at capturing ambient light, which is why one engineer compared them to a second skin. Not all of that is technological advancement. It’s mature design.

There are still difficulties, of course. Compared to silicon, perovskites are less stable, particularly when heated or exposed to moisture. Practical deployment was severely hampered by the early versions’ quick degradation. However, scientists have come up with more clever packaging in response, experimenting with durability-extending chemicals and encasing films in protective layers. Compared to where things stood just five years ago, several of these new designs have lasted more than a year without suffering a significant loss in efficiency.

Then there’s the lead problem. If the material degrades, it could be an issue because it is present in trace amounts in some perovskite formulations. However, this problem is also being solved. Even in cases when the material is deteriorated, a number of producers now employ barrier layers that capture lead and stop leaks. Like how we’ve handled lithium in batteries, it’s a workable solution, if not a flawless one.

In the meantime, other businesses are merging silicon and perovskites to produce tandem cells, which are stacked layers that produce more energy. Oxford PV recently introduced a panel with a conversion rate that is about 20% greater than conventional silicon models. This hybrid strategy strikes a compromise between durability and efficiency, providing a way forward as materials science develops.

However, the most fascinating aspect may not be technical at all. It is cultural. We’re approaching a time where solar energy just becomes a part of your daily routine and doesn’t require construction. Your jacket serves as a source of power. It turns your tent into a generator. Your presence during the day, your walk, and your commute can all contribute to energy rather than merely consume it.

Areas with minimal infrastructure benefit most from that kind of change. People have the option to wear their own power rather of waiting for a grid. These materials provide an immensely useful feature: autonomy, which can be used in emergency situations, on remote job sites, or even in cities with limited power.

This concept was expertly highlighted in Panasonic’s Expo display. Solar glass panels that were fashioned into artwork also served as energy sources. The message was very clear: energy may be incorporated into living rather than being applied to structures.

With Japan making large investments in perovskite technology, the ambitious goal is to produce 20 gigawatts of solar energy by 2040, with flexible cells playing a key part. This includes investing in entrepreneurs, providing manufacturing subsidies, and generating demand through urban improvements. If successful, it might put surface-integrated solar and wearable technology at the center of Japan’s clean energy policy.

Thus, in addition to subtly cooling bodies, charging phones, and illuminating communities, these paper-thin solar strips are also revolutionizing the concept of solar power itself. Large panels and fixed systems are no longer important. It’s all about movement, clever textiles, and tiny surfaces.