It sounds more like a design drawing from a different era than a working reality—a chip that doesn’t spark, doesn’t heat up, and requires no electricity at all. However, researchers have started to construct such gadgets covertly and slowly. They do not sparkle, nor do they hum. They do, however, compute.

In one design, a system of tiny valves, channels, and droplets takes the place of transistors. The Canadian engineers that unveiled these fluidic microchips in 2025 employ fluid or compressed air to represent ones and zeroes rather than electrical signals. Instead than using voltage differentials, logic gates are made by precisely timing the push of liquid against chambers that resemble pistons.

Such a technique is especially useful in highly sensitive situations, such as deep space, radiation zones, and MRI scanners. These chips don’t get hot. Neither of them short circuits. When conventional electronics just don’t work, they work amazingly well and are impervious to electromagnetic interference.

They also don’t need constant electricity. A small tank or portable pump can sustain sufficient air pressure to power the logic cycles. That becomes more than just a convenience in situations where batteries cannot be changed, such as inside the body. It’s necessary.

The physics of computing is challenged by photonic chips, while fluidic chips reinvent its mechanics. These chips use light to transport electrons rather than copper. Inside complex optical circuits, beams bounce, overlap, and cancel out to produce the same logical results while using a fraction of the heat and a lot more speed.

| Innovation Type | Description |

|---|---|

| Fluidic Microchips | Use compressed air or liquid logic instead of electricity for computation |

| Photonic Microchips | Use light waves (photons) to perform calculations with minimal power usage |

| First Demonstrated | Fluidic chips (2025, Canada); Photonic chips (Lightelligence, Lightmatter) |

| Key Advantages | Radiation immunity, no overheating, ultra-low power, speed of light logic |

| Potential Applications | Space missions, implanted medical devices, edge AI, secure communication |

| Power Requirements | None for logic; may need fluid pressure or minimal light source |

| Notable Research Labs | Cornell University, Lightelligence (Singapore), Lightmatter (California) |

The way they address one of the biggest inefficiencies in contemporary computing—moving data from memory to the CPU and back again—makes them very creative. Photonic systems do not require complicated back-and-forth communication because memory and logic can take place in the same physical area.

Photonic chips are capable of doing computations that would otherwise require thousands of digital processes by utilizing optical interference. Particularly in low-latency scenarios like autonomous navigation, drone cooperation, or real-time diagnostics, they are incredibly dependable and efficient.

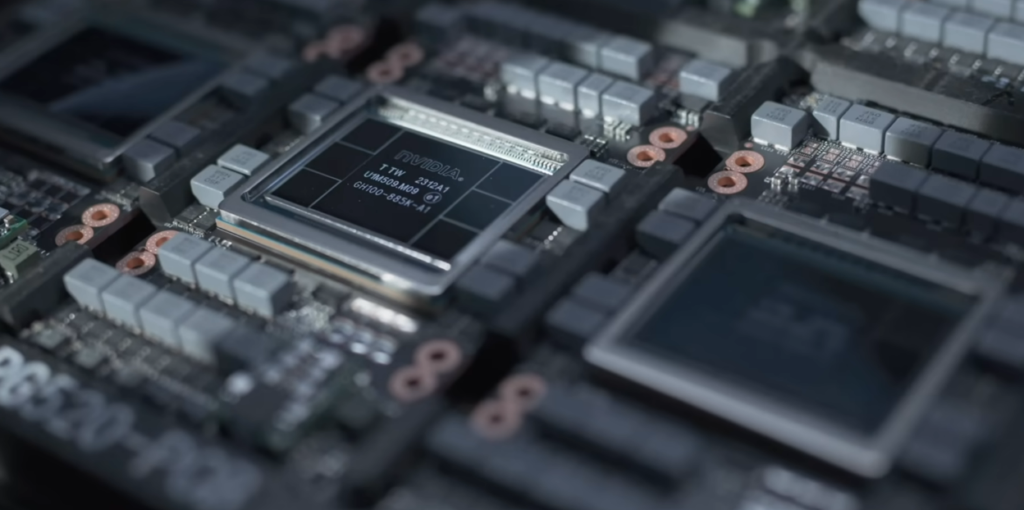

Advanced AI workloads can already be solved by a large-scale photonic processor that Lightelligence has demonstrated. A chip that could play old Atari games, read movie reviews, and create Shakespearean verse was demonstrated by another company, Lightmatter. The results were remarkably close to those of the most advanced GPUs.

A third paradigm, a hybrid architecture known as the “microwave brain,” was introduced by Cornell engineers. It can identify wireless communications or detect anomalies with less power consumption because it processes data across broad radio-frequency bands using silicon’s tunable waveguides. It’s a chip that can listen as well as compute.

When I read that chip could track radar data while using less energy than a refrigerator lamp, I stopped and wondered how many small-scale activities we’ve overwhelmed just because we didn’t challenge the concept.

The nature of these alternative chips is nonlinear, in contrast to digital circuits that scale linearly—more power equates to increased performance. Microwave band tuning, light wave harmonics, and pressure dynamics all affect how they behave. Because of this, they are remarkably adaptable to certain situations and have unexpectedly low energy costs.

Limitations exist. For example, the analog behavior of photonic chips may impair accuracy a little. With the tools available today, they are also challenging to produce on a wide scale. There are software and engineering challenges in integrating them into today’s mostly electronic hardware architecture.

The advantages are indisputable, though. These chips could significantly increase the lifespan of remote medical devices, where battery life is limited and heat is hazardous. A chip that doesn’t require electricity could prove revolutionary for space missions that travel farther than solar power. The potential uses for wearable technology, edge AI, and climate monitoring in remote areas are growing.

Replacing electricity everywhere is not the goal here. It involves putting calculation where it has never been done before. Rather of developing speedier circuits, experts are reconsidering the definition of “processing.” By doing this, they are subtly expanding the concept of intelligence itself, shifting it from the cloud to areas that are accessible by light and fluid but not by current.

More academics are now concentrating on rethinking the original purpose of transistors rather than trying to fit more transistors onto a silicon wafer. It is a strategy based on going beyond Moore’s Law rather than following it.

If these patterns keep changing over the coming years, we might not witness any dazzling ads or new gadget releases. However, we’ll start to see gadgets that live longer, malfunction less frequently, and function where nothing could before. And we’ll never forget that this change started with less authority, not more.