A drone hovers low and delays its approach in a peaceful Oregon woodland. But it does something remarkably natural—it perches—instead of thumping to the ground or hovering until its charge runs out. With a falcon-inspired mechanical grasp, its talons close quickly and embrace the branch. What appears to be effortless is actually a meticulously planned dance of anatomy, code, and physics.

This drone, created by Stanford engineers, takes inspiration from birds’ instincts rather than just imitating their flying. The project is called Stereotyped Nature-Inspired Aerial Grasper, or SNAG for short. Slow-motion video of parrotlets jumping from perch to perch was shown first. What the researchers found was striking: the birds always made the identical landing motion on any surface, whether it was wood, foam, or Teflon. Without hesitation. Just have faith in their hold.

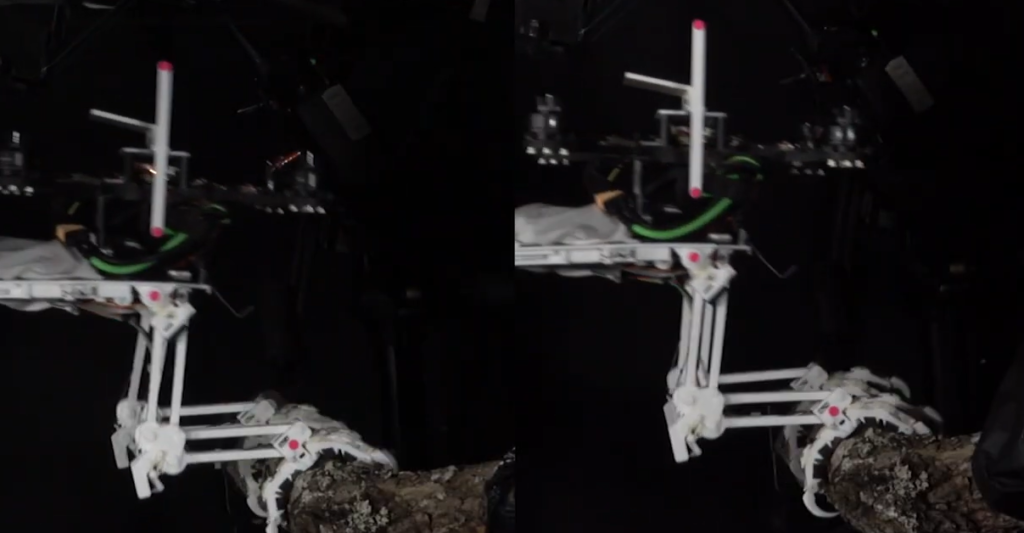

It takes more than brilliant software to replicate that confidence. The peregrine falcon-inspired legs of the SNAG drone are 3D printed and equipped with two motors and a fishing-line tendon system. The leg is swung by one motor while the other produces an incredibly strong grasp that closes in 20 milliseconds. That’s quicker than most people blink, and it’s definitely quick enough to catch a tennis ball in midair.

However, SNAG is defined by the subtlety of stillness as much as by speed. The drone uses a built-in accelerometer and a unique balancing algorithm to lock into position once it is perched. This enables it to stay steady on uneven surfaces, such as a swaying rope or a mossy limb. In one example, it attached itself to a wire and held on steadily. The accuracy was remarkably avian.

| Item | Detail |

|---|---|

| Project Name | SNAG (Stereotyped Nature-Inspired Aerial Grasper) |

| Developed by | Stanford University (Cutkosky & Lentink Labs) |

| Lead Author | William Roderick, PhD, Stanford University |

| Perching Mechanism | Based on peregrine falcon legs with motors and fishing-line tendons |

| Application Areas | Search and rescue, wildfire monitoring, environmental research |

| Real-World Testing Location | Oregon forest |

| Published In | Science Robotics, December 1, 2021 |

| External Link | https://engineering.stanford.edu/news/engineers-create-perching-bird-robot |

William Roderick, the PhD candidate responsible for most of the construction, set up a functional lab in his parents’ basement during the epidemic. Equipped with improvised test apparatus and unwavering resolve, he conducted experiments that would ultimately become fundamental. I pictured him working in dim light, assembling fishing-line tendons as the wind rustled through the Oregon trees outside.

The group created something especially novel by establishing this innovation in animal biology. SNAG has the ability to pause, in contrast to conventional drones that require flat surfaces or hover continuously. It is able to relax. New missions are made possible by that pause, such as checking humidity levels in wildfire zones or surreptitiously monitoring endangered species. Its landing is an invitation to see, not merely a maneuver.

The foot structure of the drone is quite adaptable. Researchers found very little difference in grip strength or agility between the zygodactyl (parrot-style) and anisodactyl (falcon-style) toe arrangements. In addition to improving drone adaptability in thick environments like rainforests or rocky slopes, that understanding alone may have an impact on future ornithological research.

This drone is now much more efficient than previous models thanks to careful design. It can perch and save energy instead of continuously expending power to hover or return to base. This energy-saving function is especially useful for long-duration missions such as acoustic monitoring or climatic data collection. Additionally, it lessens noise pollution because a silent drone doesn’t harm wildlife.

The SNAG team achieved a leap that feels both straightforward and innovative by utilizing the biomechanics found in nature. Control loops, geometry, and stability are the main concerns of traditional robotics. The lessons of nature—flight learnt from birds leaping through trees, trusting their toes, rather than from textbooks—are where this drone begins.

Although biomimicry has gradually become more prevalent in robotics over the last ten years, few projects have successfully combined functionality and elegance like this one. at addition to being mechanical wonders, SNAG’s talons are extremely successful at transforming drones from alien invaders into a part of their surroundings. That kind of integration is really important at a time when ecological disruption is becoming a major worry.

In one test, the drone silently perched for hours while measuring temperature and humidity in a microclimate research. It would have been challenging to map minor changes in forest health using conventional equipment or noisy, human-operated devices, but the data helped. In this case, the robot not only supported the investigation but also blended in with the surroundings.

The ramifications of SNAG in environmental study are wide-ranging. In places where scientists cannot readily deploy stationary monitors, such as the canopies of tropical forests, ledges in isolated mountains, or power lines during storm recovery efforts, lightweight, perch-capable drones may become indispensable. Instead of taking the place of scientists, they broaden their scope.

Engineers, conservationists, and policymakers have all taken notice of the initiative since it was published. It appeals to people who want technology that is more sensitive to the ecosystems it enters and feels less intrusive. Perhaps what distinguishes SNAG from previous drone initiatives is that empathy is ingrained in the design.

The future of SNAG is still being worked out. In order for the drone to land intelligently and select its perch without human guidance, Roderick and his colleagues are currently investigating autonomous navigation. By using machine vision technologies that identify optimal landing locations—branches with the proper thickness, alignment, and stability—that step would be much enhanced.

Drones like SNAG have the potential to subtly transform fieldwork in the years to come. They won’t speed noisily overhead or make a dramatic swoop. Like birds, they will land gently, then pause and pay attention. observing rather than interfering.

That vision has a certain humility—technology is perching rather than yelling. blending in with the surroundings rather than controlling them. The future is worth seeing. Naturally, quietly.