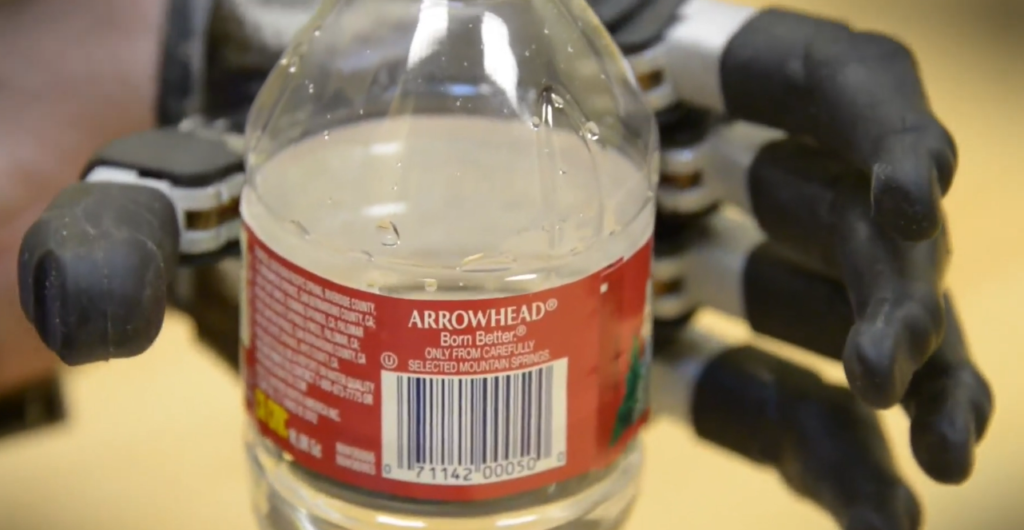

A blinded guy named Fabrizio extends his prosthetic hand over a number of bottles arranged on a table in a quiet facility nestled away in Lausanne. Each has a varied temperature; some are room temperature, others are chilly, and some are hot. He touches them one by one, pauses a while, and then identifies which is which. Visual cues are absent. He is guided only by his senses.

What’s amazing? His prosthetic hand is sensing as well as moving.

With MiniTouch, a palm-sized add-on, the user can sense a sensation in the phantom limb by translating temperature from a robotic fingertip. The technology replicates warmth or coolness where the real hand once was by sending a signal to the residual limb, in this example, Fabrizio’s upper arm. This signal is mapped back to the missing fingers by the brain, which is highly adaptable. And the outcome seems genuine.

Researchers are creating prosthetics that experience rather than just grasp or lift by utilizing methods from material engineering and sensory neurology. This change, which marks a move from mechanical assistance to sensory-rich bodily extensions, is especially novel.

| Feature | What It Enables | How It Works | Current Status | Key Benefit |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Electronic Skin | Sensation of temperature, pressure, and texture | Sensors convert stimuli to nerve signals | In clinical trials | Improves natural touch |

| Neural Interfaces | Communication between prosthetic and nervous system | Implanted or surface electrodes | Experimental | Restores limb-body connection |

| MiniTouch Device | Thermal feedback without surgery | Senses temperature and stimulates skin | Successfully tested | Differentiates hot, cold, materials |

| Haptic Feedback | Non-invasive touch simulation | Vibration or mild stimulation | Used in research prototypes | Enhances user control |

| Multimodal Integration | Combined sensory experience | Pressure + temperature + texture | In development | Mimics real-life sensation |

Many of these developments are based on the surprisingly straightforward idea that the brain retains information. The brain keeps a clear map of the lost limb even after it has been amputated. The brain frequently reassigns signals to the missing hand or foot when it receives reliable, regular signals, even if they are given in unexpected locations.

This research is quite promising because of this.

Temperature and pressure sensors are integrated into paper-thin electronics used in the artificial skin under test. It reacts to touch by producing electrical outputs that can be converted into nerve stimulation. Some groups are taking it a step further by using implanted electrodes to connect these sensors to nerve endings, especially in Italy and Switzerland. Others, such as the MiniTouch group, are using non-invasive methods that offer very clear input at a low risk of surgery.

Both paths are worthwhile. Neural integration and high fidelity may be preferred by certain users. Others might put cost, use, or safety first. The fact that the field is currently supporting both ways is good.

When I read about an amputee who uses just temperature signals to discern between metal and plastic, it really got to me. It made me realize how frequently we take these small encounters for granted, despite the fact that they influence how we perceive the physical world.

Touch is more than just functionality for amputees; it’s safety, familiarity, and connection. Imagine being able to determine whether your tea is hot enough or whether a child’s forehead is warm. Emotional health can be significantly impacted by these minute things. The advancement here feels so profoundly human because of this.

These technologies are advancing impressively quickly to the clinical testing stages thanks to smart collaborations between neuroscientists, engineers, and physicians. Instead of completely replacing current prosthetics, devices like MiniTouch are being incorporated into them, making adoption more simpler and, perhaps, more common.

However, not all users react in the same way. While some people have little trouble experiencing thermal phantom experiences, others do not. It is still a scientific challenge to fine-tune this response. However, these obstacles are being significantly lowered thanks to the quick development of flexible electronics and AI-assisted brain mapping.

Prosthetics may provide multiple sensations in the years to come, including softness, friction, and even vibration intensity. This is already being tested in certain labs, which combine artificial muscle systems with e-skin to produce limbs that react dynamically to movement and surfaces.

This could lead to new opportunities in intimacy and work for early adopters. A more responsive limb is a source of confidence as well as a useful tool.

These sensory prosthesis were developed more quickly during the pandemic because to remote trials. Quick iterations and design improvements were made possible by the engineers’ ability to get real-time feedback from people testing prototypes at home. Need has intensified that speed, and it hasn’t halted.

Many of the new sensor materials are inexpensive, which is very advantageous. Today’s prosthetic sensors are surprisingly inexpensive and incredibly durable, in contrast to the bulky and delicate early models. This could someday enable mass production, giving patients access to enhanced functionality that they previously couldn’t afford.

Some prosthetics now learn from their users through the integration of AI and sensing technologies. In addition to adjusting grip force and heat sensitivity, they may also identify trends in daily activities. This degree of personalization, which is still in its early stages, suggests that prostheses will eventually improve abilities rather than merely restore them.

Perhaps the greatest revolutionary change will come from this subtle revolution in sensory repair. not just for the functional benefits it provides, but also for the emotional healing it provides.

A prosthetic becomes more than just a piece of equipment when it can provide the feeling of a wind, a warm handshake, or the soft weight of a pet.

It reawakens into recollection.

And perhaps the most amazing development of all is that.