In France’s scientific corridors, a new rhythm is taking shape. Public laboratories are increasingly accepting collaborators from the business sector, venture-backed startups, and international innovators, when formerly they functioned in academic isolation. The slow but steady change is indicative of a national strategy: transform scientific advancements into a shared economic impetus.

One of the best examples of this change is the Servier Research and Development Institute, which is located on a large 45,000-square-meter site in Paris-Saclay. It is more than just a structure; it is a metaphor—a tangible representation of teamwork in which entrepreneurs and PhDs work together to solve challenges. Saclay is establishing a standard as one of Europe’s most active research areas by skillfully fusing private risk-taking with public expertise.

The scientific quality of France’s public labs was praised for decades, but they had trouble translating their findings into goods or services. Due to a lack of finance or commercial focus, projects that should have grown frequently remained on the shelf. Today, that trend is being purposefully turned around. Government-led programs and customized incentives have greatly shortened the time it takes to bring a prototype to market.

Policy is the foundation for this change. Labs are becoming launchpads because to the French government’s strategic IP-sharing schemes and organized co-research subsidies. Companies are encouraged to collaborate with public organizations like CNRS and CEA as co-authors of innovations rather than as contracted consultants. Startups receive equipment, guidance, and incredibly easy access to international networks in exchange.

| Category | Detail |

|---|---|

| Initiative Purpose | To bridge the gap between academic innovation and industrial application |

| Main Drivers | Economic competitiveness, funding diversification, technology transfer |

| Government Support | IP-sharing incentives, spin-off programs, joint public-private research platforms |

| Major Research Hubs | Paris-Saclay, CNRS, CEA, University of Paris-Saclay, École Polytechnique |

| Notable Industry Partner | Servier R&D Institute (Paris-Saclay) and Spartners BioLabs Incubator |

| Research Focus | Life sciences, health tech, clean energy, defense innovation, digital manufacturing |

| Economic Vision | France aiming for technological sovereignty through agile, collaborative ecosystems |

A research ecosystem that resembles a co-working campus rather than a fortress is the end product. For example, biotech firms can grow rapidly at Spartners by Servier & BioLabs without the typical financial burden because they share lab space with fully furnished benches. Approximately fifteen early-stage businesses are housed in the incubator; each was chosen for its scientific potential and compatibility with Servier’s therapeutic agenda.

These partnerships are influencing the course of research itself, not merely being convenient. Scientists are better able to comprehend the urgency of certain diseases, supply chain gaps, or sustainability obstacles when they collaborate directly with industrial partners. This realization frequently results in solutions that are socially and commercially necessary in addition to being sound technically.

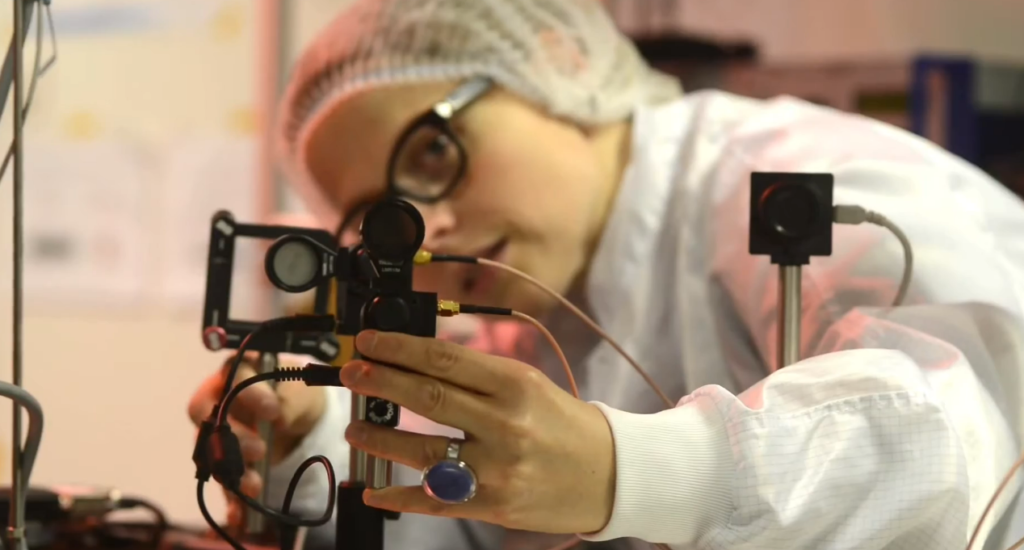

I heard a junior scientist at the Saclay campus one calm afternoon describe how she changed her synthesis technique after a feedback session with a startup. I was struck by how frequently research advances not only via money but also through conflict and being in the presence of someone who needs what you’re creating.

These collaborations in the lab are quite successful in highlighting those kinds of situations. They expedite trial cycles, refine theories, and—possibly most crucially—create mutual accountability between previously isolated sectors. With a focus on technical sovereignty and global competitiveness, France understands that these partnerships are increasingly necessary rather than discretionary.

Additionally, this approach contributes to France’s larger goal of luring in foreign talent. Hubs like Paris-Saclay are growing in popularity as researchers from the United States and other regions look for more welcoming, encouraging surroundings. They provide not just jobs but also a sense of purpose with their state-of-the-art infrastructure, biodiversity labels, and green-certified buildings.

The statistics support the narrative. Currently accounting for 15% of French research output, Paris-Saclay is predicted to reach 25% in the next years. Currently, public-private partnerships account for over 40% of R&D employment in the Greater Paris region. From data analytics companies to defense contractors, the number of affiliated partners continues to expand.

This is an improvement rather than a change from public research. Although fundamental science is still pursued in labs, the focus is on applications. Research gets repurposed, but its integrity is preserved. A particularly unique national template has been created by combining wiser regulation, strategically placed incubators, and noticeably increased research throughput.

Although it is doing this experiment in a disciplined manner, France is not alone. It is fostering a generation of businesses whose origins start not in garages but in high-security labs, alongside Nobel laureates and PhD candidates, by integrating entrepreneurs directly into the nation’s knowledge base.

The consequences go beyond new product releases or patents. Since scientific connections frequently outlive political ones, they have an impact on education, local jobs, and even diplomacy. Through this development, France is subtly redefining the role of its public research facilities as two-way bridges rather than ivory towers.