The transition was revealed with little warning, but the ramifications spread across decades. When the pension age for women rose to coincide with that of males, it wasn’t the legislation itself that provoked public anger—it was how it was presented. Or more correctly, how it wasn’t.

Millions of women who were born in the 1950s assumed that they would start to retire at age 60. Their designs, which were based on that standard, were very similar for every household. Many had quietly quit the workforce early or taken on caring obligations, trusting in the schedule they’d been provided. Suddenly, that assurance was stripped away.

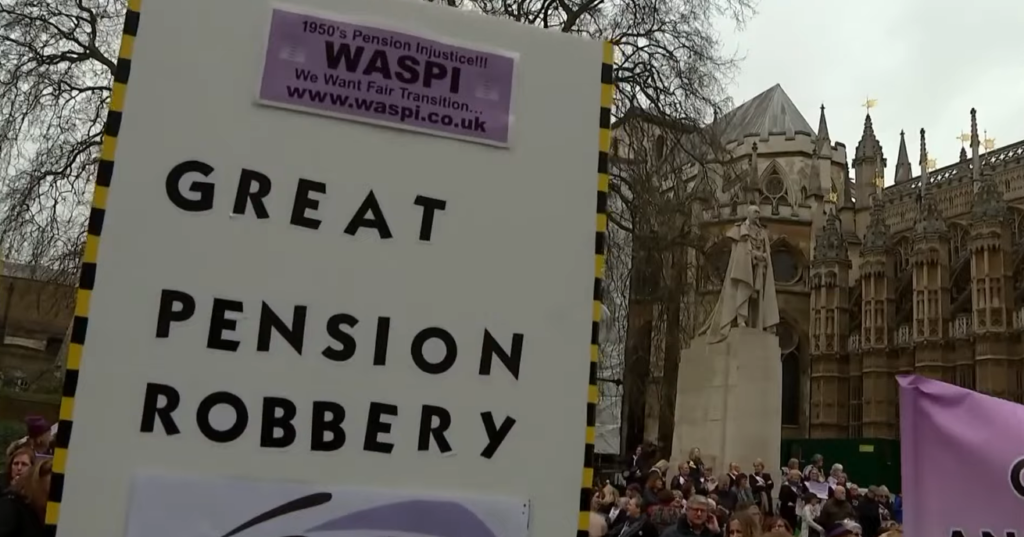

The WASPI movement—Women Against State Pension Inequality—was not created out of ideology. Administrative quiet gave birth to it. These women were not disputing justice in age alignment; they were objecting to a lack of time to prepare. Even if the move was legal, the ineffective communication of it has had disastrous social and financial effects.

In recent days, the administration confirmed its refusal to offer compensation, despite assessing new information. A rejection in 2024 preceded this one, and the results were remarkably identical. While an apology was given again, it came without redress.

| Key Context | Details |

|---|---|

| Issue | WASPI women pension compensation rejection |

| Affected Group | Women born between 1950–1960 |

| Government Position | No compensation; apology issued for communication failure |

| Estimated Number of Affected Women | 3.6 million |

| Estimated Compensation Cost | £10.5 billion |

| Parliamentary Ombudsman Recommendation | Compensation of £1,000–£2,950 per individual |

| WASPI Campaign Status | Considering legal action; seeking justice through courts and Parliament |

| External Link | WASPI Official Website |

Pat McFadden, the Secretary of State for Work and Pensions, conceded that letters should have been sent sooner. Yet he asserted that most women were already aware of the change—citing advertisements, brochures, and public campaigns. But awareness isn’t uniform. Information slid between bill inserts or displayed in general practitioner clinics should not be used in place of a direct letter to the person in question.

WASPI chair Angela Madden referred to the decision as “a disgraceful political choice,” saying that the government had “magically found billions” for other priorities in a short period of time. Her annoyance makes sense. Campaigners are not calling for full pension restoration—they are demanding for compensation based on maladministration admitted by the Parliamentary and Health Service Ombudsman.

Through the use of a focused public narrative, the government presented the problem as one that was both practically and financially challenging. Yet the Ombudsman’s recommendation—between £1,000 and £2,950 per impacted woman—was far from excessive. This would be more than simply money for 3.6 million women; it would be recognition.

It’s not hard to understand why so many women feel overlooked. They were the generation who worked without equal pay protections, who took time off without maternity leave, and who now confront retirement with a lighter purse and higher load. Many were pushed into financial precarity not through poor preparation, but through being denied the option to plan at all.

Two years ago, I had a brief conversation with a woman in Cornwall. In 2018, she had imagined she could retire from her little home-based sewing business. She described how it felt like the “floor had quietly given way” when she learned that her pension had been postponed by many years, months before she turned sixty.

That feeling resonates across WASPI groups. The betrayal by process is the source of the resentment, not the policy.

The government’s rationale depended primarily on assumptions about communal knowledge. McFadden noted that public messaging had been “exceptionally clear” across numerous media outlets. However, clarity is only important when it is heard at the appropriate moment. For many, the vital information came not from the DWP but from friends, internet forums, or newspaper reports discovered too late.

This case is very instructive in terms of public accountability. Maladministration happened, the government acknowledged. It admitted that there were problems with the messages’ timeliness. And yet, it argues that the women affected experienced “no direct financial loss.” Despite its scientific structure, this remark seems tone deaf. Even so, indirect loss is a loss. Confidence in one’s retirement, the capacity to downsize gradually, the option to leave a career at 59—all of that has worth.

WASPI has transformed from a modest campaign into a potent collective voice through smart campaigning and increasing public empathy. Now that they are looking into their legal options, they are resolved to take their issue to the courts if necessary and move past legislative apologies. Their message is straightforward: seeking retribution is a duty, not a charitable act.

Some MPs have rallied in support. In addition to disregarding the Ombudsman’s conclusions, denying compensation also calls into question the legitimacy of independent oversight, Labour’s Rebecca Long-Bailey reminded Parliament. Steve Darling, a Liberal Democrat MP, went so far as to say that the issue had been thrown into the “too-hard-to-do” pile, which is a political euphemism for silent desertion.

Rejection hurts more than simply the money. It is reputational. It reminds women that even when the system gets it wrong, even when that error is acknowledged, justice is not guaranteed. That reality is more difficult for many than the missing cash.

The tone of the pension argument has shifted, but it still exists. The way a country treats the people it once pledged to protect is now more important than its policies. If governments hope to earn the trust of their constituents, they must be willing to acknowledge when that trust has been betrayed.

A new dilemma emerges in the upcoming months as WASPI develops its legal case and advocates press for discussion: how can a democratic government admit wrongdoing while refusing to provide a remedy? If nothing else, this case will create a precedent for how silence is considered in policymaking.