A humanoid robot is increasingly being seen leading karaoke, stretching, or triggering memory games in a variety of languages on weekday mornings in Singapore’s active ageing centers. Not only does Dexie, the AI-powered robot that many seniors are now familiar with, teach, but it also encourages without becoming tired, reprimanding, or forgetting who someone is.

A nationwide movement has emerged from what started as a number of isolated trials. With the formal launch of AI-powered elder care robots throughout its eldercare infrastructure, Singapore has completely changed the way seniors interact with healthcare, memory, mobility, and company.

This change isn’t ornamental. It has its roots in the haste of the population. More over 20% of Singaporeans will be 65 years of age or older by 2026. Healthcare staffing shortages, which were made worse by the pandemic, have made it abundantly evident that traditional methods are insufficient.

Singapore is aggressively redefining how aging is supported—emotionally, physically, and cognitively—by making early and generous investments in robotic support systems. This is in addition to increasing access to care.

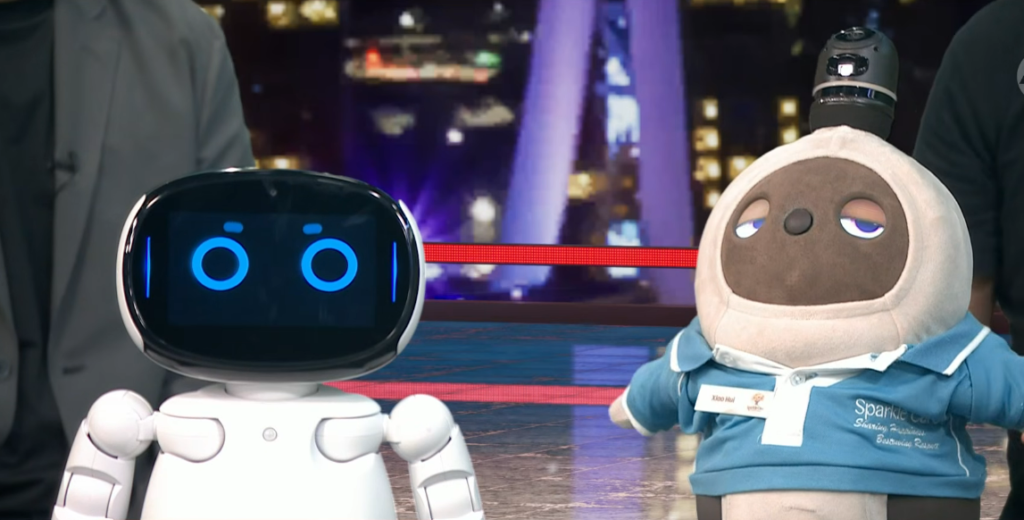

The functions of the robots differ greatly. Dexie’s song, dancing, and bingo are all designed to encourage group interaction. A smaller unit called Kebbi is meant to be interactive; inhabitants can dance and solve puzzles together. Seniors with dementia now frequently sit calmly in their laps with Paro, a therapeutic seal that reacts to touch and voice and makes soft sounds when stroked.

| Item | Details |

|---|---|

| Initiative | National Rollout of AI-Driven Elder Care Robots |

| Country | Singapore |

| Key Technologies | Companion robots, AI-powered exercise trainers, fall detectors |

| Notable Robots | Dexie, Kebbi, Paro, RoboCoach Xian |

| Supporting Institutions | Lions Home, St Luke’s ElderCare, Bishan Home, Synapxe, SoundEye |

| Primary Goals | Promote active aging, reduce isolation, assist caregivers |

| National Funding | Over S$1 billion invested into AI development (2024–2029) |

| Rollout Timeline | 2026–2027 |

| Primary Challenges | Cost, digital literacy, cultural adaptation, data privacy |

| Reference | CNA, Straits Times, SUTD, MOH Singapore, AIC |

These tools are supporting the practical and emotional structure that enables workers to provide deeper care, not taking the place of humans. Seniors like Albert Yeo at St. Luke’s ElderCare have started co-authoring their autobiographies with AI-powered apps that use spoken instructions. Grandchildren now read the stories the program creates from voice reflections with quiet interest. Many of these stories have been put into souvenir volumes.

My attention was drawn to Mr. Yeo’s seemingly innocuous statement: “I told my story to the robot, and it somehow made it sound like poetry.” He didn’t sound sardonic or amused. He truly felt proud.

Caregivers can spend more time doing the tasks that truly call for intuition, like listening, consoling, and inspiring, by using robotic systems to manage high-frequency, low-skill interactions, including checking in on health status, directing mild exercise, or even starting conversations.

Technology is also enhancing the infrastructure for safety and diagnosis. Without the use of cameras or wearable technology, a local business called SoundEye has created wall-mounted sensors that can identify erratic movement or distress sounds. When their new smart ceiling light, AURI, senses a fall or an odd noise, it instantly turns on the lights in the room and notifies caregivers. Seniors living alone, a situation that is becoming more and more prevalent, benefit greatly from this type of system.

Care facilities in Singapore are also incorporating increasingly advanced monitoring technologies. For example, the AMI Intelli program is being piloted by Bishan Home for the Intellectually Disabled. The system gauges residents’ emotional and cognitive levels by watching how they engage with conversational AI and play certain digital games. The trend-based insights give staff members a better understanding of how situations change over weeks rather than just during clinic visits.

Compared to traditional check-ins, this type of longitudinal observation is far more revealing. It provides a deeper knowledge of the person behind the patient by going beyond fleeting facts and into pattern recognition.

When considered from the perspective of community use, many programs have turned out to be unexpectedly economical. Thousands of dollars for a single robot can seem like a lot, but when distributed throughout a facility, the cost per user drastically decreases. Furthermore, their return on investment becomes incredibly evident when taking into account their involvement in lowering hospital admissions, decreasing falls, and identifying early indicators of mental impairment.

With the help of public funds and strategic alliances, Singapore is establishing itself as a pioneer in eldercare AI. Over the course of five years, more than S$1 billion has been allocated to the development of AI. A large portion of funding is going toward domestic solutions like HealthHub AI, a multilingual chatbot that offers reliable health advice in Tamil, Mandarin, Malay, and English.

Naturally, there is considerable cultural reluctance to allow machines to play such personal roles. While some elders find robotic interaction a little unsettling, others are concerned about privacy. However, when carefully crafted—with welcoming movement, local dialect understanding, and warm tones—these technologies have turned out to be quite welcome.

For many people, trust is earned by the small things. They are called by name by robots. interfaces with Singlish recognition. interfaces that feel familiar rather than alien. These kinds of features are identity-affirming in addition to being user-friendly.

Human staff continue to play a crucial role. As dementia care specialist Ms. Prudence Chan said, while robots may initiate a session, staff members are the ones who bring the period to a close with a smile, a touch, or a shared memory. Robots make space. People fill it.

Another layer is added by Lions Befrienders’ IM-HAPPY and IM-ALERT programs. During home visits, a tablet camera is used to evaluate facial expressions in order to identify early indicators of distress. The other uses games to assess cognitive response. These programs discreetly gather data that enables caregivers to take action before issues worsen and turn into emergencies.

Seniors are becoming more proactive about their own health, even within their own homes. SUTD’s Neatsens smart fabric project measures gait, balance, and step counts using electrical signals from wearable knitted clothing. Twenty-five seniors have previously tried a prototype knee brace. Physiotherapists have been able to modify routines with the use of its feedback, improving the accuracy and efficacy of therapy.

Seniors benefit from initiatives like this by feeling more empowered during their own recuperation and by being able to stay out of hospitals for longer. They provide more than simply help; they provide you the chance to age with agency.

Of course, there are still ethical issues. Researchers are working hard to address these important issues: over-reliance, privacy, and expense. SoundEye’s sensors, for instance, employ non-identifiable data and steer clear of cameras. Anonymization is incorporated into the design architecture from the beginning, ensuring the security of health information.

The sound of an 86-year-old citizen impatiently waiting for Dexie to begin announcing bingo numbers is a softer sound that can be heard beneath the code and sensors.

He once told a reporter, “I don’t like robots.” “However, I enjoy her playing bingo.”

That straightforward acknowledgement sums up what many technologists aim to do: develop technologies that blend in with their surroundings and make consumers feel noticed. For robots to be useful, they don’t have to be exact replicas of people. All they have to do is arrive, react thoughtfully, and blend in with lives that are still full of rhythm, story, and regularity.