Portugal has adopted a stance that feels both realistic and subtly audacious in recent years. Rather of erecting ever-higher concrete walls along its Atlantic coast, it is posing the question of whether cities themselves ought to adjust and become floating instead of battling. Despite its subtlety, that change is very novel and compelling.

The percentage of people who live close to the coast is close to 60%, and it increases significantly every summer. At rates very similar to those of other erosion hotspots around southern Europe, beaches in the north and the Algarve are retreating. Sand retreats of up to two meters annually in certain places have reshaped neighborhoods and jeopardized tourism revenue, which is still very helpful to local economies.

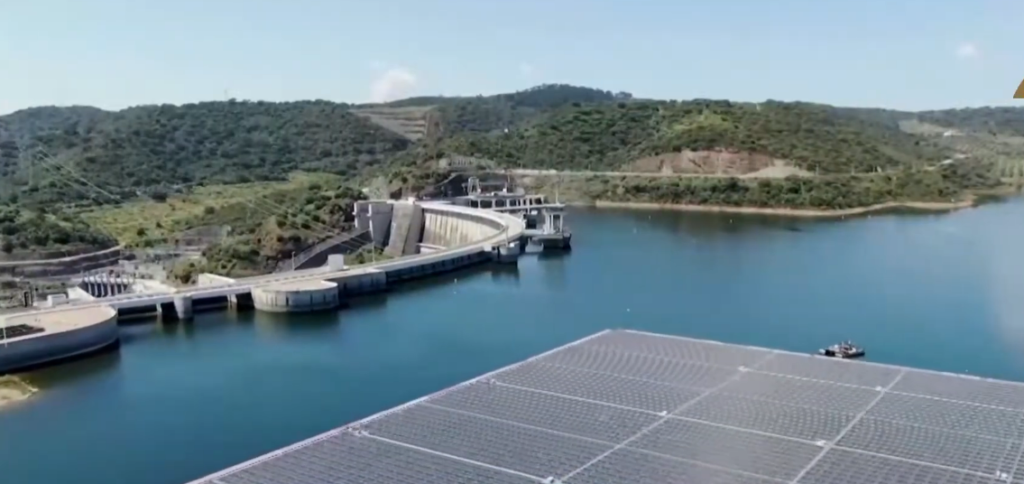

The urgency of Lisbon’s coastal planning discussions has increased significantly over the last ten years. Instead of concentrating on breakwaters, engineers are now talking about buoyant foundations and modular platforms, as well as floating districts that might rise with the tide. The conversation has been reframed from defense to adaptation with remarkable success.

The SOS Climate Waterfront initiative was started in 2019 and is at the heart of this change. Working with partners across Europe, Lisbon started experimenting with small-scale floating structures constructed from shells, algae, and salvaged marine materials. Despite their modest look, these prototypes are purposefully flexible and highly versatile.

| Topic | Details |

|---|---|

| Country | Portugal |

| Focus | Floating infrastructure and climate-resilient coastal living |

| Lead Projects | SOS Climate Waterfront, Coastal Resilience Hubs, Nature-Based Solutions, BoSS initiative |

| Key Cities | Lisbon, Amadora, Matosinhos, Águeda, Guimarães |

| Primary Risks Addressed | Sea-level rise, coastal erosion, high-density coastal population |

| Supporting Programmes | EU Horizon, New European Bauhaus |

| External Source | https://projects.research-and-innovation.ec.europa.eu |

The pale surface of a demonstration unit made partially of oyster shells caught the afternoon light as I stopped by it last October while strolling along the Tagus estuary. It appeared less like a futuristic show and more like a sensible next step, subtly indicating a surprisingly peaceful future.

Portugal is using satellite data and AI modeling to track erosion and forecast flood patterns through strategic research partnerships. These systems function similarly to a swarm of bees, continuously collecting information, comparing signals, and instantly updating risk profiles. When new risks arise, coastal authorities can react much more quickly by utilizing modern analytics.

Local leaders are guiding neighboring municipalities in disaster risk reduction in Amadora and Matosinhos, which have been recognized as Resilience Hubs. By simplifying processes and releasing resources, their tactics have significantly enhanced coordination between environmental scientists and urban planners. Adaptation initiatives were previously hampered by bureaucratic delays, but this method is quite effective.

Equally important to the strategy are solutions derived from nature. The installation of permeable pavements and green corridors in Águeda and Guimarães is absorbing runoff and lowering the risk of flooding. Although these procedures are not particularly ostentatious, they are incredibly dependable and long-lasting.

Regarding climate adaptation, Portugal’s approach seems surprisingly well-rounded. Officials are experimenting with smaller, increasingly scalable units rather than making a firm commitment to large floating megastructures right once. This gradual approach is especially useful for managing public funds while upholding public confidence.

Another layer connects sustainability and culture with the Bauhaus of the Seas Sails initiative. Chefs and students in Lisbon are creating meals inspired by the marine ecosystems in the area by experimenting with menus based on estuaries. Through the integration of coastal preservation and food systems, governments are expanding the concept of resilience beyond architecture.

During a community workshop, I observed a group of youngsters sketch solar-powered floating schools. Their designs were unexpectedly practical and reasonably priced. The passion in the audience was very evident, piercing the technical language that frequently muddies discussions about climate change.

Portugal’s urgency is also shaped by its coastline memory. A historical reminder of unexpected vulnerability, the 1755 earthquake and tsunami are still deeply ingrained in the national memory. Together with current climate projections, such legacy has developed a culture that emphasizes readiness without fear.

If enlarged, floating structures would be dependent on circular waste management and renewable energy systems. While cutting-edge recycling systems would turn garbage into useful resources, lowering emissions and material costs, solar panels and wind turbines might create energy independence for these communities. Such platforms, if properly designed, would be incredibly robust and resilient to storm surges.

The economic ramifications are encouraging for coastal firms. Modular floating units are being investigated by construction companies because they may be assembled much more quickly than conventional coastal constructions. Anchoring devices that are incredibly dependable even when subjected to high wave pressure are being designed by maritime startups.

Critics raise valid concerns about accessibility and affordability. Floating housing must continue to be shockingly affordable for middle-class families in order to prevent it from turning into an exclusive community. It seems that policymakers are conscious of this, since they have designed pilot initiatives that emphasize community ownership and diversity.

Public involvement has significantly improved since the start of the initial experimental initiatives. Previously skeptical residents now participate in workshops, sharing their thoughts and concerns about adaption strategies. Despite its slow pace, this civic engagement is especially novel in bolstering democratic resilience.

Portugal’s approach could not result in immediately recognizable buildings. Rather, it is creating a framework that is extremely effective, technologically savvy, and culturally aware. Other coastal nations are starting to take a careful look at the model the nation is creating by moving gently rather than drastically.