Ronald Loaiza seemed unfazed by the rain. Just after six in the morning, he came at the Cartago voting place wrapped in his jacket, silently pleased to be among the first in line. “It’s very important that we exercise the right that this country gives us,” he remarked. His sentiment, gently articulated, echoed across a country that found itself at a pivotal moment.

By evening, the Supreme Electoral Tribunal had revealed early numbers, and the verdict was becoming remarkably clear. With almost 49% of the vote, Laura Fernández, a 39-year-old conservative supported by President Rodrigo Chaves, had taken the lead. The centrist economist trailing behind with 33%, Álvaro Ramos, made a swift and non-dramatic concession and pledged to be a watchful but constructive opponent.

That deliberate, democratic act demonstrated a civic maturity that has recently been put to the test domestically but is frequently praised internationally.

Fernández greeted the triumph not with excitement, but with striking clarity. Her remarks, delivered with calm confidence, impacted with unexpected force: “The mandate is clear. The transformation will be deep and irreversible.” She promised to construct Costa Rica’s “third republic,” a concept that brought praise but also worry. There was no disguising that this was more than a turnover of power—it was a continuation, and escalation, of Chaves’ populist program.

| Element | Detail |

|---|---|

| Election Date | February 1, 2026 |

| Presidential Winner | Laura Fernández (Sovereign People’s Party) |

| Vote Share (Preliminary) | 48.9% |

| Closest Challenger | Álvaro Ramos (National Liberation Party) – 33.3% |

| Runoff Needed? | No – Fernández surpassed the 40% threshold |

| Legislative Seats | Sovereign People’s Party projected to win 30 of 57 seats |

| Outgoing President | Rodrigo Chaves (endorsed Fernández) |

| Voter Turnout | Approx. 3.7 million eligible voters |

| Key Election Issue | Rising crime and national security |

| Notable Policy Pledge | Completion of maximum-security mega-prison |

| Credible Source | AP News Report |

The security-first agenda dominated the campaign. Violent crime has grown significantly, driving citizens from cautious caution into open frustration. Homicide rates reached historic highs in 2023. The country long recognized for its political stability—frequently referred to as the “Switzerland of Central America”—now found itself battling with criminal networks, escalating drug violence, and eroding trust in judicial institutions.

Fernández, who served under Chaves as Minister of the Presidency, vowed action. She committed to complete the maximum-security mega-prison her predecessor had started, and talked in favor of mandatory jail labor. These stances resonated strongly in metropolitan centers, particularly among younger people irritated by government inaction and the rising normality of insecurity.

I remember seeing her address supporters the night the polls closed, her voice calm, almost calculated. At that moment, what struck me wasn’t her rhetoric—it was the quiet conviction with which the throng took her every word.

Critics, however, caution that promises of order can easily shade into dictatorship. Fernández thinks her changes will remain within democratic norms. But the opposition, while congratulatory, has vowed to remain attentive. Ramos, in his capitulation, reminded the public that “criticizing is allowed.” It was more of a silent appeal than a comfort.

With 20 presidential contestants on the ballot, the campaign had long appeared divided. Yet no one but Fernández and Ramos achieved even 5%. That lopsided outcome offers a strikingly efficient picture of voter intention: Costa Ricans didn’t simply lean toward continuity—they embraced it firmly.

Fernández’s party, the Sovereign People’s Party, is anticipated to win a majority in the National Assembly, climbing from just eight seats to thirty. While short of the supermajority needed to alter judicial appointments or constitutional revisions, it’s a noticeably improved position. It affords her a parliamentary base strong enough to govern forcefully, though not unfettered.

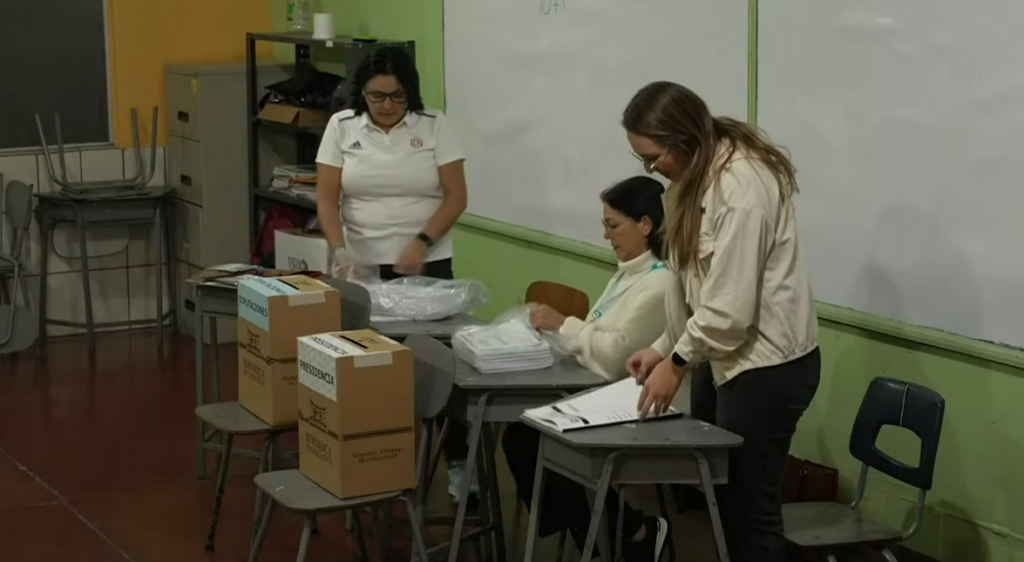

The day itself went smoothly. Despite sporadic showers, voting stations continued to run smoothly. From the highland communities of Cartago to the Pacific coastlines, the act of voting felt almost ceremonial—routine, yet laden with implication.

At one polling location, a grandmother in her 60s gently escorted her grandson through the procedure, quietly explaining each step. That intergenerational moment—a grandma transferring civic knowledge to a child—was a little reminder of how democracies are preserved not just via elections, but through inherited habit.

President Chaves, whose term expires later this year, conveyed sincere greetings to Fernández. His unwavering support during the campaign was crucial. Despite varied assessments on his governance—praised by some for directness, slammed by others for divisiveness—his brand remains effective.

Chaves, an outsider, triumphed four years ago. His legacy is now carried on and rebranded by Fernández, who offers a comparable aggressive approach but with a more technocratic polish. Whether this change signifies evolution or entrenchment remains to be seen.

Analysts have been speculating in recent days about whether this election represents a more profound change—a hardening of the populist movement or just a reaction to an overburdened legal system. Either way, Costa Rica has elected to keep the course, but with a more resolute grasp on the steering wheel.

Through smart messaging and intensive ground campaigns, Fernández presented herself as both heir and innovator. That blend—familiarity with a promise of reform—proved particularly powerful.

Her opponents may disagree on policy, but even they agreed her tactic was, by political standards, extremely effective.

As the dust settles, Costa Rica is not at a crossroad, but mid-turn. The question now isn’t simply where the country is going—but how fast it gets there, and at what democratic cost.