It began in silence. Journalists and policymakers began to feel uneasy that Japan’s scientific infrastructure, which had previously been a driving force behind advancement, had begun to stall—not with news conferences or political hoopla. That unease quickly solidified into a course of action. A strategic academic combination between Tokyo Tech and the Tokyo Medical and Dental University, which resulted in Science Tokyo, marked a turning point.

This merger was not for show. It was an effort to reconsider the organization of research, the dissemination of information, and the ways in which Japanese universities might change without losing their cultural roots. The new organization served as a spark for significant shifts in the research environment in the capital.

Cross-disciplinary clusters called “Visionary Initiatives” were created by Science Tokyo to address issues like clean energy, healthy aging, and pandemic resistance. These descriptors aren’t only thematic. Underpinned by a shared research objective, each VI is staffed by scientists, engineers, social theorists, and graduate students. It’s a particularly creative approach that creates bridges where there were previously moats and breaks through departmental silos.

| Key Initiative | Detail |

|---|---|

| Visionary Initiatives (VIs) | New research hubs uniting disciplines across science, medicine, and engineering |

| Flagship Merger | Tokyo Tech and Tokyo Medical and Dental University formed Science Tokyo in 2024 |

| Infrastructure Modernization | Investment in energy-smart buildings and AI-driven lab systems |

| International Collaboration | Strategic partnerships with ASEAN, EU, and industry leaders |

| Quantum Computing Milestone | University of Tokyo installed IBM Quantum System One |

| Open Access Research Mandate | Government requires publicly funded research to be free by April 2025 |

| Education-Research Integration | Graduate students embedded directly in Visionary Initiative projects |

| Long-term Goal | Involve all 1,800 full-time researchers in integrated, interdisciplinary work by 2028 |

Students now have a very different experience. Graduate researchers are no longer confined to the sidelines or had to wait for lab availability; instead, they are integrated into VIs from their first semester. Their research is linked to practical demands rather than merely academic theory, and they receive mentorship from cross-functional teams. This structure is quite adaptable and not only empowering for scientists in their early stages.

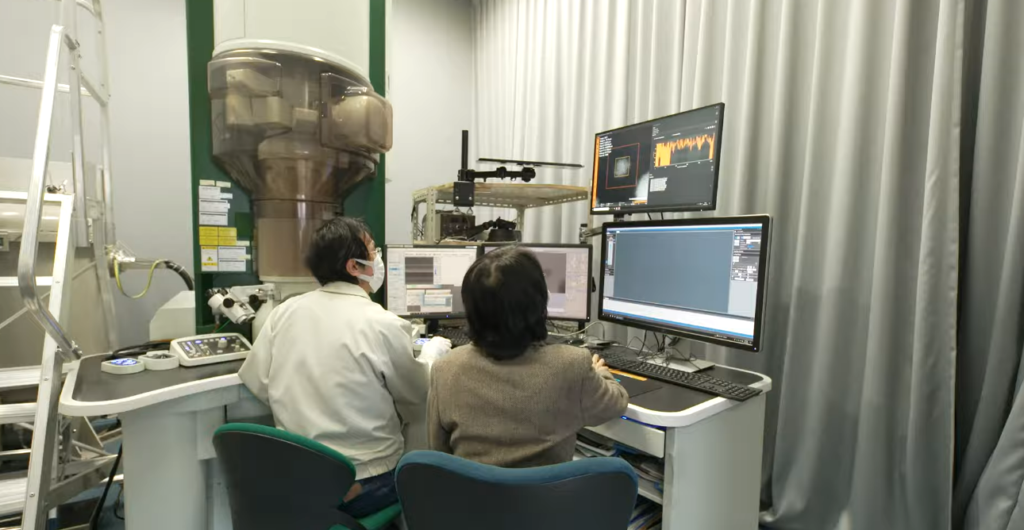

The government has made significant investments to go along with this cultural change. In the last two years, AI-managed systems have been installed on major campuses throughout Tokyo to optimize energy use, schedule equipment, and organize inventory—tasks that formerly required countless human hours. These labs are being constructed with longevity in mind. Exceptionally robust, the architecture is built to support future expansions without requiring major renovations.

When IBM’s Quantum System One was installed at the University of Tokyo, Japan became one of the few countries with operational quantum computing capability, marking a significant milestone. Researchers studying cryptography, biology, and finance are using that machine, not keeping it hidden in some ivory tower.

The institutions in Tokyo are also reaching beyond of Japan through strategic alliances. They are actively creating a cooperative network that represents Japan’s changing academic and diplomatic aspirations by connecting with ASEAN institutions and research facilities in Europe. In rapidly evolving fields where local knowledge is no longer adequate, these international connections are especially helpful.

I observed a group of researchers honing a predictive AI model for elder care on a visit last autumn. Though impressive, the technology wasn’t what stuck with me. It involved medical students working alongside robotics engineers and elder care professionals, each of whom brought insights informed by their own training. It brought to mind how effective study may be when human need—rather than merely academic curiosity—is at its center.

Instead of trying to catch up, Tokyo is trying to change the course of the race. The city is creating a modular, future-ready research ecosystem, something few have dared to try, by completely reorganizing its research structure. Instead than needing to undergo bureaucratic reinvention every few years, it can adapt to evolving technologies.

Significantly better faculty arrangements are starting to appear. A professor’s reputation is based on both their publication productivity and their ability to work across fields. By increasing research efficiency without significantly increasing hiring, this small change has had a remarkably low cost.

But there are still issues. Smaller private universities are having difficulty keeping up the pace. Many are unable to fully implement the VI model due to a lack of funding or faculty size. There are government assistance programs in place, but the disparity across institutions is growing. The benefits of this renaissance could focus solely on Tokyo if nothing is done.

In spite of these differences, the momentum is increasing. The analysis of pathology slides using AI is incredibly reliable. Sweat samples are being used to create new biosensors that can identify early indicators of neurological problems. These biosensors are incredibly effective and shockingly inexpensive.

Global citations have significantly increased for Japanese researchers since open-access rules were implemented; this is a metric that has a direct impact on funding and institutional reputation. It’s a straightforward adjustment—making research freely accessible—but it has greatly lowered obstacles for up-and-coming researchers and international partners.

The long-term perspective is possibly the most encouraging. More research isn’t the only aim. It’s superior research: work that stays rooted in social purpose, predicts the complexity of the actual world, and uses public funding extremely efficiently.

The vertically integrated research paradigm that Tokyo is creating by integrating participation at all levels—from first-year graduate students to seasoned researchers—reflects the lean, flexible, and impact-oriented nature of startups. It differs from conventional academic frameworks that set thinking and action apart.

The researcher who casually remarked, “We’ve stopped waiting for the next great lab,” stands out in my memory the most. Our decision is to construct it ourselves. That sentiment encapsulates what is subtly emerging in Tokyo’s universities.

No revolution has been proclaimed on stage. Change is taking place one lab, one student, and one multidisciplinary project at a time. And in the upcoming years, it might provide a model for any city that wants to continue to be not only competitive but also significantly influential in determining the direction of science.