At one point, the Beachy Head skeleton appeared ready to change people’s perceptions of ancient Britain by pointing to an unexpected and varied past that contradicted preconceived notions. After being stored for decades, the astonishingly complete skeleton of a young woman from the Roman era was rediscovered in 2012 in the archives of Eastbourne Town Hall, capturing the public’s and scientists’ attention in unexpected ways. Over the course of more than ten years, what started as a solitary archeological discovery has developed into a powerful illustration of how science gradually adds to itself, refuting earlier theories as techniques advance.

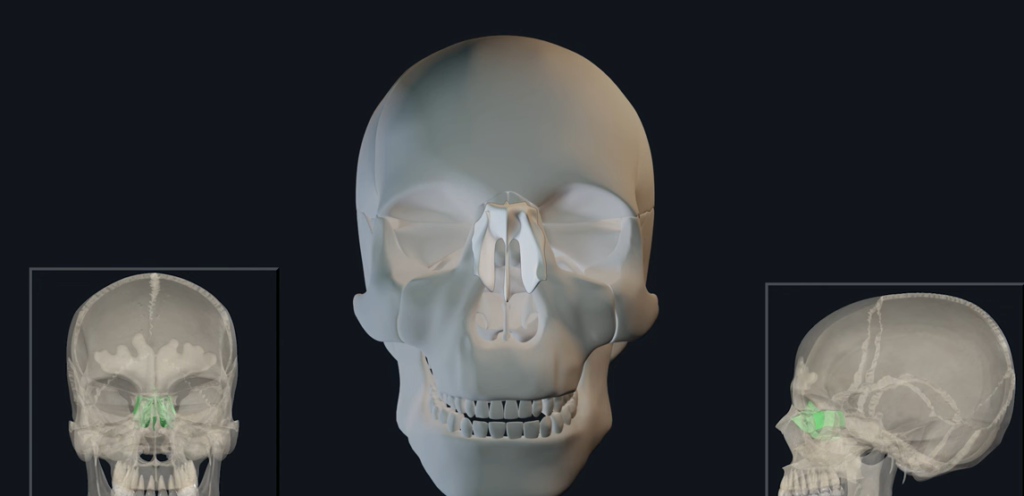

Because they believed she was discovered close to East Sussex’s spectacular chalk cliffs, which are renowned for their breathtaking beauty and geological prominence, archaeologists originally called the remains the Beachy Head Lady. She may have had sub-Saharan African heritage, according to early evaluations based on skull shape, a result that had significant cultural resonance at the time. It alluded to diversity in Roman Britain that had not yet been recorded, a concept that struck a chord with academics and historians and even appeared in television documentaries. However, as study progressed, the narrative started to change and that interpretation became less certain.

More cautious genomic research in 2017 revealed a Mediterranean connection—possibly Cyprus—complicating previous assertions while maintaining a feeling of global origin. These fluctuating theories were more indicative of developing methods, each iteration building on the last, than they were of confusion. By the end of 2025, researchers had a far better understanding of her genetic background because to greatly enhanced DNA sequencing technology. Her ancestry is clearly closer to southern England, not Africa or the Mediterranean, according to the new information. This was a watershed moment that profoundly altered the scientific narrative.

| Detail | Information |

|---|---|

| Name | Beachy Head Woman (also referred to as Beachy Head Skeleton) |

| Discovered | c. 1950s, Beachy Head, East Sussex, UK |

| Rediscovered | 2012, in a box at Eastbourne Town Hall |

| Estimated Period | Roman Era, approx. 125–245 AD |

| Age at Death | Around 18–25 years old |

| Initial Origin Hypotheses | Sub-Saharan Africa → Cyprus → Southern England |

| Height | Approx. 4’9” to 5’1” (145–155 cm) |

| DNA Finding (2025) | Genetically British with blue eyes, fair hair, light skin |

| Dietary Indicators | Likely consumed seafood, based on carbon and nitrogen isotope analysis |

| Injury Evidence | Healed leg wound indicating a non-fatal trauma |

| Research Institutions | Natural History Museum, UCL, Liverpool John Moores University |

| Public Display Location | Eastbourne Museum’s Beachy Head Story Centre |

| External Link | Wikipedia – Beachy Head Lady |

One of the participating geneticists said, “This is what scientific progress looks like,” highlighting how the discipline has benefited from enhanced reference genomes and sophisticated analytical methods that were just not accessible ten years ago. Researchers can now definitely trace her genetic ties to local people in Roman-era Britain thanks to the significant improvement in precision of modern ancient DNA analysis over earlier techniques.

Although some could see this as a retraction, it’s preferable to think of it as refining, with each new piece of data adding depth to a more complex picture of her life. Using the example of tracking weak constellations in a sky that becomes more visible with modern telescopes, I remember seeing a colleague explain how she might have lived. Her identity emerged not as a static fact but rather as a constellation made up of numerous data points.

With fair hair, light skin, and blue eyes—features that physical anthropology and face reconstructions now confirm—the young woman most likely grew up in southern England, according to the new DNA profile. She was just about five feet tall and between the ages of 18 and 25 when she passed away. Carbon and nitrogen isotope study of her bones indicates a diet high in seafood, probably from the nearby coastal environment. By bridging the gap between biology and ecological context, these nutritional hints provide a remarkably similar sensation of everyday existence.

A healed wound on her leg is among the most moving features of her remains. It suggests that she endured a serious injury long enough for her body to heal, which speaks to resiliency and healing. That tiny bone scar gives us a glimpse of lived experience and serves as a reminder that, like people today, ancient people were molded by daily struggles and physical hardships.

Crucially, this improved knowledge not only updated her ancestry but also highlighted the need for interpretation to be adaptable as new information becomes available. Craniometry, the early application of skull morphology, was a common method for determining ancestry. However, given its historical abuse in attempts to categorize human populations, academics are now more conscious of its limitations. Contemporary genomic methods are more reliable and yield insights that are more in line with the complex patterns of local variation and human migration.

The Natural History Museum and University College London, two organizations that participated in the study, have emphasized how every technological development contributes to a rewriting of the tale and strengthens a dedication to truthfulness and openness. Their research reflects a larger scientific mindset: curiosity and improved instruments may lead to revisions to our current understanding of the world.

The removal of a plaque that originally honored her as “the first Black Briton,” a designation based on past evaluations, has generated public discussion. While some local historians lamented the move, others used it as a chance to talk about how history is constantly being rewritten as new information becomes available. It serves as a reminder that historical accounts are dynamic creations that change as our understanding of them as a society deepens.

The Beachy Head skeleton narrative is comforting since it shows scientific self-correction in action as a strength rather than a fault. Both the general public and academics have followed the research with an increasing understanding of how evidence builds up and becomes more clear over time. Furthermore, the continuous reinterpretation has not lessened her significance for museums; rather, it has elevated her to the status of a symbol of the way that earlier populations lived, traveled, and engaged with their surroundings.

This reminds us that people from centuries ago were just as biologically and culturally diverse as those alive now, and it promotes a wider discussion about how we interpret historical remains. The refined roots of the Beachy Head skeleton do not lessen her relevance; rather, they enhance our knowledge of the local populations in Roman Britain. Her narrative is not one of mistaken identity but rather of scientific advancement and growing awareness.